Black Portuguese millipede

Ommatoiulus moreletii

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

Rises in black Portuguese millipede populations in recent seasons are likely due to increased uptake of no-till practices and stubble retention. Reduction of paddock stubble during summer may reduce numbers. The presence of millipedes in crops does not necessarily mean damage will occur. Preventative action is a key part to control as there are limited management options after crop-emergence. These millipedes have a shiny, cylindrical and dark coloured body and will curl into a spiral or thrash about violently when disturbed.

In recent years black Portuguese millipede damage to emerging canola crops has increased.

Occurrence Top

Black Portuguese millipedes are native to Europe and were accidentally introduced into Australia in the mid 1950’s to become a common pest found in South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania, New South Wales and Western Australia.

Wet summers in the recent past have led to increases in populations in some areas and the growing of more susceptible crops has seen a corresponding increase in damage.

Description Top

Black Portuguese millipedes have a smooth, cylindrical body made up of 50 segments when fully developed. Adults are 30-45 mm long, dark grey to black in colour and have 2 pairs of legs on most body segments. Juveniles are light brown with a darker stripe along each side of their body.

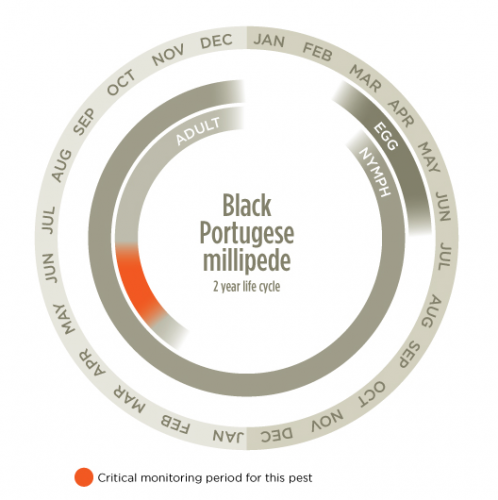

Lifecycle Top

Black Portuguese millipedes commence mating in March/April and lay most eggs in April/May. Adult females lay about 200 yellowish-white eggs into the soil. Immobile and legless juveniles hatch from eggs and develop over a week into the first active stage. Body segments and legs are added with successive moults as they grow through 7, 8 or 9 stages in the first year. After this they moult only during spring and summer. During moulting they are particularly vulnerable before their cuticle or skin hardens. They reach adult size (tenth or eleventh life stage) and maturity after approximately 2 years.

Behaviour Top

Black Portuguese millipedes congregate in large numbers and become quite mobile and conspicuous after the first rains in autumn. A temperature range 17-21°C and humidity of around 95% favour activity. Millipedes feed on organic material including leaf litter, damp decaying wood, fungi and plant roots, mosses, green leaves on the soil surface and pollen. They have a role in breaking down soil organic matter. Due to their feeding habits they accumulate in higher numbers where there is undisturbed leaf litter and organic mulch, or where winter weeds create an almost unbroken ground cover. When disturbed they either curl up in a tight spiral or thrash about trying to escape.

Millipedes can move several hundred metres a year and are transported from one property to others and to new locations in plant material and farm machinery.

Similar to Top

Although it may be confused with native species, the smooth, cylindrical body of the black Portuguese millipede distinguishes it from these native species.

Native species tend to be widespread in low numbers while the black Portuguese millipedes are found in high numbers.

Crops attacked Top

Predominantly canola, but will also attack cereals crops.

Damage Top

Crop feeding damage is relatively rare and somewhat unusual as black Portuguese millipedes generally feed on organic matter such as leaf litter, decaying wood and fungi. There are many instances where high numbers of millipedes are present in a paddock but no crop damage occurs. Black Portuguese millipedes occasionally attack living plants by chewing the leaves and stems. In canola, they remove irregular sections from the leaves, and can kill whole plants if damage is severe. Damage to cereals can also occur when the stems of young plants are chewed. There is some evidence that millipedes feed on crop plants when they are seeking moisture. There have been suggestions that millipedes feed on crop plants to access moisture when moisture is limited.

Monitor Top

Black Portuguese millipedes are mostly active at night and most problematic to emerging crop seedlings. Inspect crops during the establishment period. During hot dry weather, they hide in the soil. Rainfall often stimulates activity of black Portuguese millipedes. During the day, it is best to search under rocks, stubble residue, wood, or to dig up the soil with a spade. Refuge traps such as carpet squares, tiles or pot plant bases can be used to detect millipedes.

Economic thresholds Top

There have been no thresholds developed for black Portuguese millipedes.

Management options Top

Biological

The parasitic nematode Rhabditis necromena was released in 1988 to parts of South Australia to provide biological control. The pest status of the black Portuguese millipede has decreased in many areas in South Australia since that time, however it is unclear how widely the nematode has spread. Natural predators such as spiders, beetles and scorpions are known to feed on millipedes.

Cultural

It is believed black Portuguese millipede numbers have increased in recent years due to increased stubble retention, which provides them with a favourable habitat. Removal of trash is an effective management strategy. Burning stubbles in paddocks known to harbor millipedes has been shown to give satisfactory control. Early sowing of high-vigour crop varieties at a higher seeding rate should help compensate for loss of seedlings.

Chemical

There are currently no insecticides registered against black Portuguese millipedes in broadacre crops.

References/Further Reading Top

Bailey P. 2004. Portuguese Millipedes Fact Sheet. South Australia Research and Development Institute (SARDI).

Baker GH. 1978. The population dynamics of the Portuguese Millipede Ommatoiulis moreletii (Diplopoda: Iulidae). Journal of Zoology 186: 229-242.

GRDC. 2013. Black Portuguese Millipedes & Slaters Fact Sheet.

SARDI Entomology. 2010. Portuguese Millipedes Fact Sheet. FS 03/10. South Australia Research and Development Institute (SARDI).

Widmer M. 2003. Portuguese millipedes (Ommatoiulus moreletii). Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia. https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/pest-insects/portuguese-millipedes

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI).

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| August 2015 | 1.0 | Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI) | Garry McDonald (cesar) and Alana Govender (cesar) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.