Armyworm

Mythimna convecta, Persectania ewingii, Persectania dyscrita

Other common names

common armyworm, southern armyworm, inland armyworm

Photo by Julia Severi, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

Armyworms are common caterpillar pests mostly of grass pastures, cereal and rice crops. The larvae are identifiable by three parallel white stripes along their body. They cause most damage to crops through defoliation in autumn and winter, but can also cause direct seed loss in spring (particularly in barley and oats) and summer (rice) through stem, spikelet and head-lopping. In the uncommon event of extreme food depletion and crowding, they will ‘march’ out of crops and pastures in plague proportions in search of food, which gives them the name ‘armyworm’.

Armyworms attack cereal crops from the early vegetative stage through to early ripening

Occurrence Top

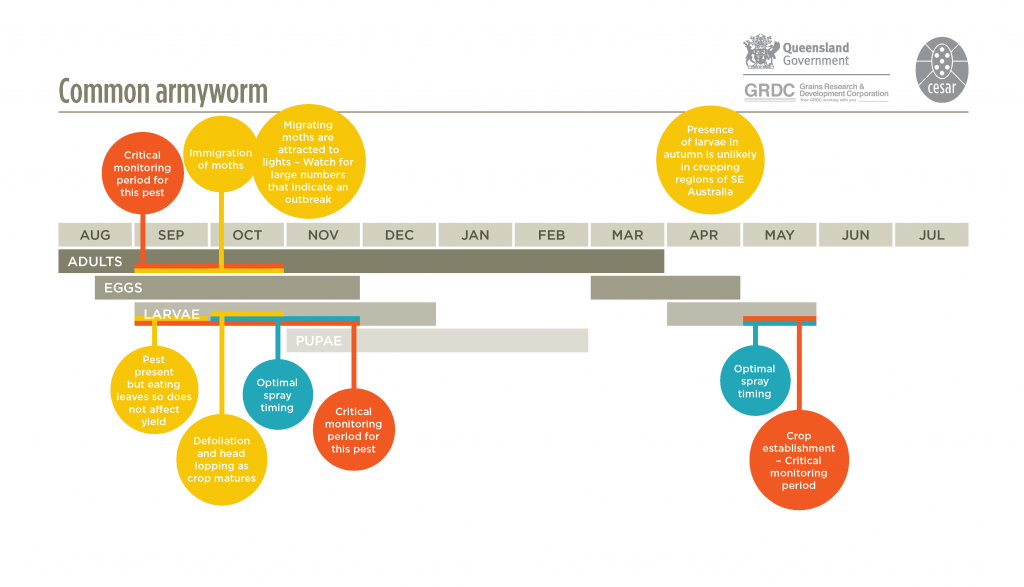

These are native pests. Common armyworm (Mythimna convecta) is found in all states of Australia and potentially will invade all major broadacre-cropping regions year round, but particularly spring and summer. The Persectania species are more typically found in southern regions of Australian autumn and winter, but their activity can sometimes extend into spring.

Description Top

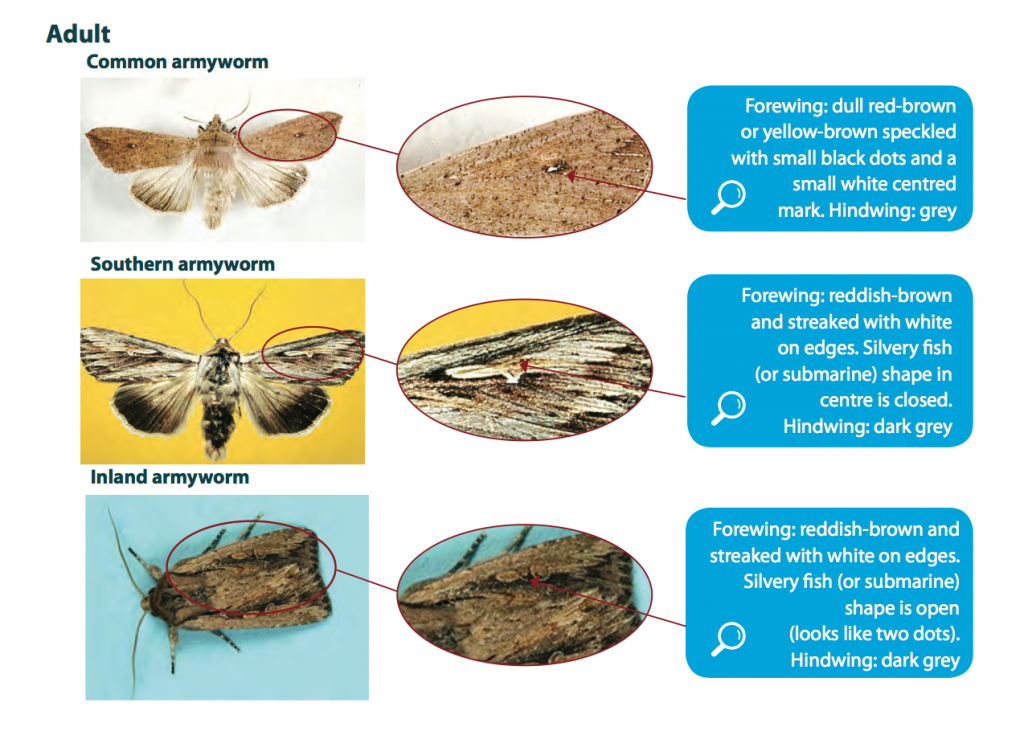

The three armyworm species commonly found in southern Australia are the common, southern and inland armyworms. Note that the common armyworm, Leucania convecta, was formally known as Mythimna convecta. They are difficult to distinguish apart, however, correct species identification in the field is generally not critical because their habits, type of damage and control are similar.

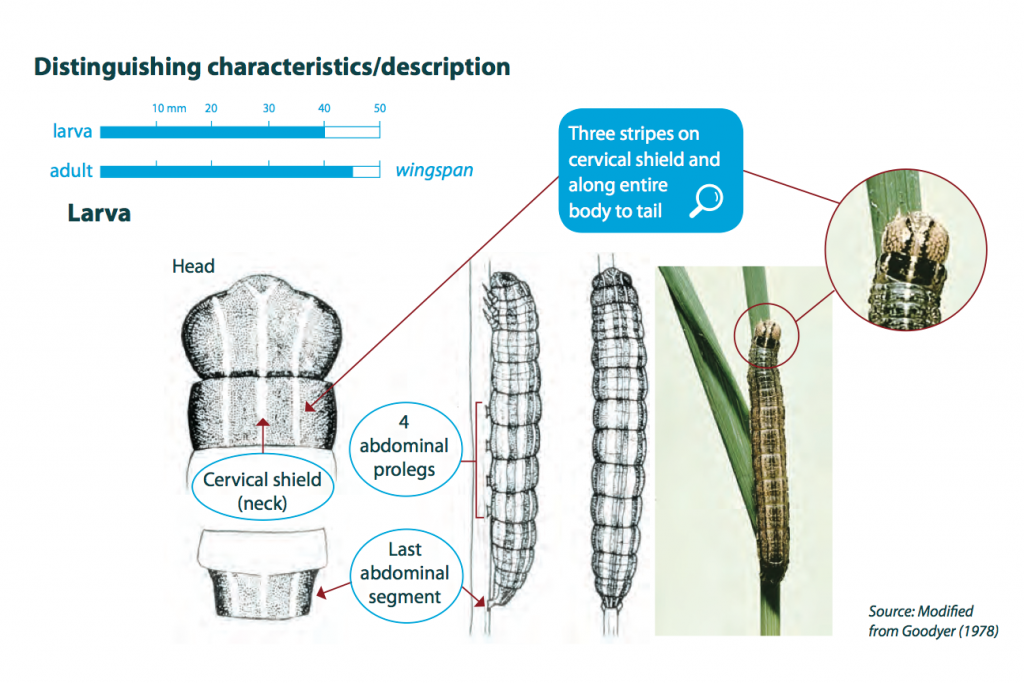

Armyworm caterpillars of all species are about 1mm long after hatching and grow up to 40 mm in length and usually have smooth bodies with a few fine hairs. Body colour can vary, but larvae are generally green, brown or yellow with three parallel white longitudinal stripes running from the ‘collar’ behind the head, along the body to the tail end. The body stripes can vary, but the collar stripes are always present. They have one pair of anal prolegs and four pairs of abdominal prolegs. Larvae live and pupate in the soil and are generally nocturnal.

Adult moths are grey-brown in colour and have a stout body with a wingspan of approximately 40-45 mm. The common armyworm migrates into south-eastern Australian cropping areas in late winter or early spring laying eggs in cereals, rice and pastures. Southern and inland armyworms, which are also migratory, are most commonly found in autumn and winter, often in relatively high densities. They can also be found damaging crops during spring in cooler regions. All armyworms lay eggs in dry grass and stubble from previous cereal crops or pasture.

Armyworms are identifiable by three parallel white stripes along their body

Lifecycle Top

Armyworm eggs are laid in batches of about 5-30, glued together in the hidden, twisted crevices of standing dried grasses, straw and stubble or sometimes in seed heads. In spring, the common armyworm will also lay in the crevices between the ligules of lower senescing leaves and stem. The eggs may take 6-20 days to hatch, depending on local temperatures. The young larvae, which are approximately 2-3 mm in length, may disperse away from the egg laying sites on fine silken threads. These are used to allow wind dispersal within a few metres of the egg-laying site.

There are six or sometimes seven stages (instars) of caterpillar growth, and the skin is shed after each. Development is faster at higher temperatures; common armyworm develops faster than southern armyworm.

Older caterpillars crawl around at night and may move up and down plants regularly. They spend the day curled up at the base of the plant under clods of soil or in the plant crown. The majority of plant damage is caused by the final larval stages.

The mature caterpillars pupate in the surface of the soil at the base of the plant. The adult moth finally emerges at least four to six weeks (possibly many more) after pupation, and migrates away from the region.

Behaviour Top

Armyworms almost always fly into crops following short to long distance migrations. After eggs hatch, they mostly feed on leaves, but under certain circumstances will feed on the seed stem, resulting in head or panicle loss. The change in feeding habit is caused by depletion of green leaf material or crowding. In the unusual event of extreme food depletion and crowding, they will ‘march’ out of crops and pastures in search of food, which gives them the name ‘armyworm’. In this state, the caterpillars become distinctively darker and will march during the day.

Adult moths are most active on warm humid evenings during spring and autumn.

Similar to Top

Larvae are similar to native budworm (more prominent body hairs) and cutworms (stripes absent or indistinct). They can also be confused with other species of armyworm that are more prominent in northern Australia including the day feeding armyworm (and other Spodoptera spp.), and other grass feeding noctuids such as species of Proteuxoa and Dasygaster spp. (herringbone caterpillars).

Crops attacked Top

Barley, oats and rice are most susceptible to economic damage, but armyworms are also commonly found in wheat, triticale and grass pastures where extreme defoliation or head loss occasionally occurs. These species generally do not damage oilseeds and grain legumes, although limited defoliation of lentils (removal of lower branchlets) has been observed. Autumn and winter infestations are almost always associated with crops sown into standing stubble, providing a medium upon which moths lay their eggs.

Damage Top

There are two periods of armyworm damage: late autumn and winter (low to moderate economic damage) and late spring (high risk of seed loss in maturing crops). Armyworm larvae feed on the leaf margins of seedling and vegetative crops causing ‘scalloping’. Larger larvae consume greater volumes of leaves, and seedlings and early vegetative crops may be completely defoliated. However, in late spring barley crops are most susceptible to damage when they are attacked near maturity. Similarly, rice is most susceptible in the later stages of crop growth when spikelets within the panicles are severed in summer. The larger larvae, which may have been in the crop for 6-8 weeks, chew through the stem just below the head (the last green material left on the plant) causing heads to be lopped and fall to the ground. Wheat and triticale have thicker stems and are less susceptible to head loss.

Damaging infestations in autumn and winter are almost always associated with crops sown into standing stubble, providing a medium upon which moths lay their eggs.

Monitor Top

Early in the season, monitor crops sown into standing stubble, as this is commonly where armyworm damage will appear first.

When cereals, pasture seed crops and rice are approaching ripening, early detection of armyworm is important. The most critical time is 3-4 weeks prior to harvest, although crops should also be monitored during tillering. Assessing the numbers of armyworms can be difficult because their movements vary with weather conditions and feeding preferences. Larvae are most active at night, although can sometimes be seen during the day feeding on leaves and stems of crops. Look for signs of caterpillar droppings (frass) and damage to plant heads. Look for caterpillars on plants and on the ground, especially under leaf litter between the rows. Check frequently for signs of head-lopping in barley, oats and rice.

There are several techniques for monitoring armyworm, each demonstrated here by a short video: a) use of a sweep net in a crop, particularly in the early evening, provides an indication of the relative densities and stages of armyworm; b) A beatsheet sampling provides a better absolute measure; and c) ground searching. Although more time consuming, ground searches provide the best indication of the imminent damage potential of large larvae.

Early monitoring of pre-ripening crops can save considerable crop loss

Economic thresholds Top

For winter outbreaks (during tillering), economic thresholds of 8 to 10 larvae per m2 provide a guide for spray decisions. For spring outbreaks (during crop ripening) spraying is recommended when the density of larvae exceeds 1 to 3 larvae per m2 although this figure must be interpreted in light of timing of harvest, green matter available in the crop, expected return on the crop, and larval development stage (McDonald 1995). In rice, recommended thresholds are 8, 12 and 16 larvae per m2 for pre-panicle formation, >2 weeks before harvest, and <2 weeks before harvest, respectively (Stevens 2013).

Management options Top

Biological

Parasitic flies and wasps, predatory beetles and diseases commonly attack armyworms, and can suppress natural populations, particularly in spring, if not disrupted by broad-spectrum insecticides. Parasitoids and beetles attack early stage larvae while late stage caterpillars and pupae commonly succumb to parasitic flies and wasps.

Cultural

Desiccating or swathing crops close to harvest will minimise armyworm damage.

Chemical

There are several insecticides registered against armyworms in broadacre crops. See the APVMA website for current chemical options. The biological insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is effective on armyworms and is also ‘soft’ on natural enemies. Spray Bt late in the day/evening to minimise UV breakdown of the product, and ensure the insecticide is sprayed out within 2 hours of mixing. Make sure the appropriate strain is used for the target pest, add a wetting agent and use high water volumes to ensure good coverage on leaf surfaces. When insecticides are required, it is recommended that applications be carried out in the late afternoon or early evening.

Biological insecticides are effective on armyworms; application should be carried out in the later afternoon or early evening.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Garry McDonald (cesar). Melina Miles and Tonia Grundy (Queensland Department of Agriculture) produced the YouTube videos.

References/Further Reading Top

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. 2012. I SPY. Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA) and the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA).

Lionel H. 2013. A history of forecasting outbreaks of the southern armyworm, ‘Persectania ewingii’ (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Tasmania. Plant Protection Quarterly 28: 15-21.

Lionel H. 2013. Long-term light trap data from Tasmania, Australia. Plant Protection Quarterly 28: 22-27.

Lionel H. 2013. The common armyworm, ‘Mythimna convecta’ (Walker) (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera), a seasonal resident in Tasmania. Plant Protection Quarterly 28: 114-119.

McDonald G and Smith AM. 1986. The incidence and distribution of the armyworms Mythimna convecta (walker) and Persectania spp. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and their parasitoids in major agricultural districts of Victoria, southeastern Australia. Bulletin of Entomological Research 76: 199-210.

McDonald G, Bryceson KP and Farrow RA. 1990. The development of the 1983 outbreak of the common armyworm, Mythimna convecta, in Eastern Australia. Journal of Applied Ecology 27: 1001-1019.

McDonald G and Cole PG. 1991. Factors influencing oocyte development in Mythimna convecta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and their possible impact on migration in eastern Australia. Bulletin of Entomological Research 81: 175-184.

McDonald, G. 1995. Armyworms. Victorian Department of Natural Resources and Environment. http://www.depi.vic.gov.au/agriculture-and-food/pests-diseases-and-weeds/pest-insects-and-mites/armyworms

McDonald G, New TR and Farrow RA. 1995. Geographical and temporal distribution of the common armyworm, Mythimna convecta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in eastern Australia: larval habitats and outbreaks. Australian Journal of Zoology 43: 601–629.

McDonald G. 1991. Oviposition and larval dispersal of the common armyworm, Mythimna convecta (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Australian Journal of Ecology 16: 385-393.

Micic S. 2015. Diagnosing armyworm. Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia. https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/mycrop/diagnosing-armyworm.

Phelps DG and Gregg PC. 1991. Effects of water stress on curly Mitchell grass, the common armyworm and the Australian plague locust. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 31: 325 – 331.

Stevens M. 2013. Armyworms in rice. Primefact 1316. NSW Department of Primary Industries.

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| February 2015 | 1.0 | Garry McDonald (cesar) | Bill Kimber (SARDI) and Alana Govender (cesar) |

| March 2016 | 1.1 | Garry McDonald (cesar) | Bill Kimber (SARDI) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.