Redheaded pasture cockchafer

Adoryphorus coulonii

Other common names

Scarab

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

A native beetle that is problematic in higher rainfall areas, redheaded cockchafer is predominantly a pest of pastures of south-eastern Australia. Typically found in higher rainfall zones, the white-grey larvae have a red-brown head capsule and adults are reddish brown to black. As larvae live entirely in the soil, chemical control is impractical particularly for the more damaging stages.

The soil dwelling larvae feed on roots of pasture plants. Severe infestations can roll back pasture like a carpet.

Occurrence Top

Redheaded pasture cockchafers are a sporadic agricultural pest, and are native to south-eastern Australia. They are most common in south-west and central Victoria, northern Tasmania, south-eastern South Australia and the southern tablelands of New South Wales, appearing to be problematic where the annual rainfall exceeds about 500 mm. They tend to be more prolific on lighter sandy loam soils. Although typically found in higher rainfall areas, they tend to occur in higher numbers and are more of a problem in drier years.

Description Top

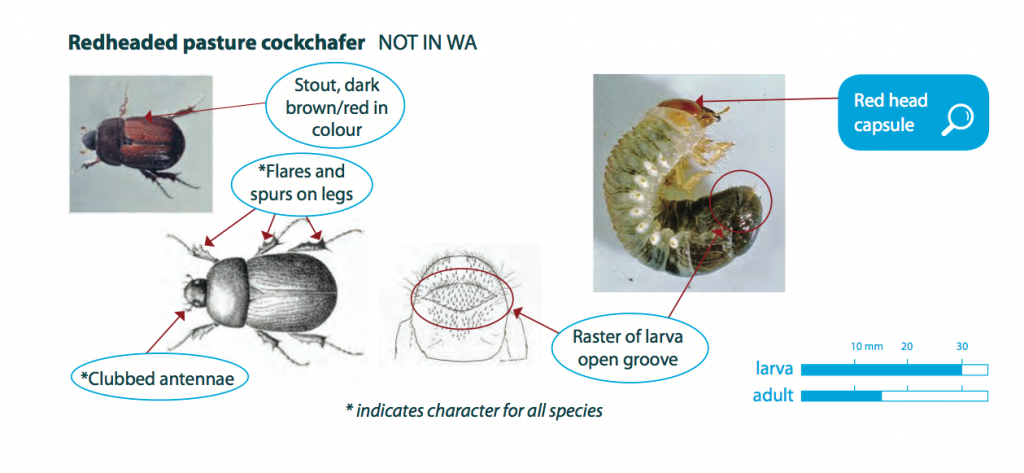

Redheaded pasture cockchafer larvae are greyish-white to cream in colour with a hard red-brown head capsule. They have soft bodies, six legs and are grub like. Fully-grown larvae are up to 30 mm long and curl into a ‘C‘-shape. Their gut contents can often be seen through the external covering in medium to larger larvae. Adult beetles are reddish-brown to black in colour, and are approximately 15 mm long and 8 mm wide. They have flares/spurs on their legs and clubbed antennae.

Lifecycle Top

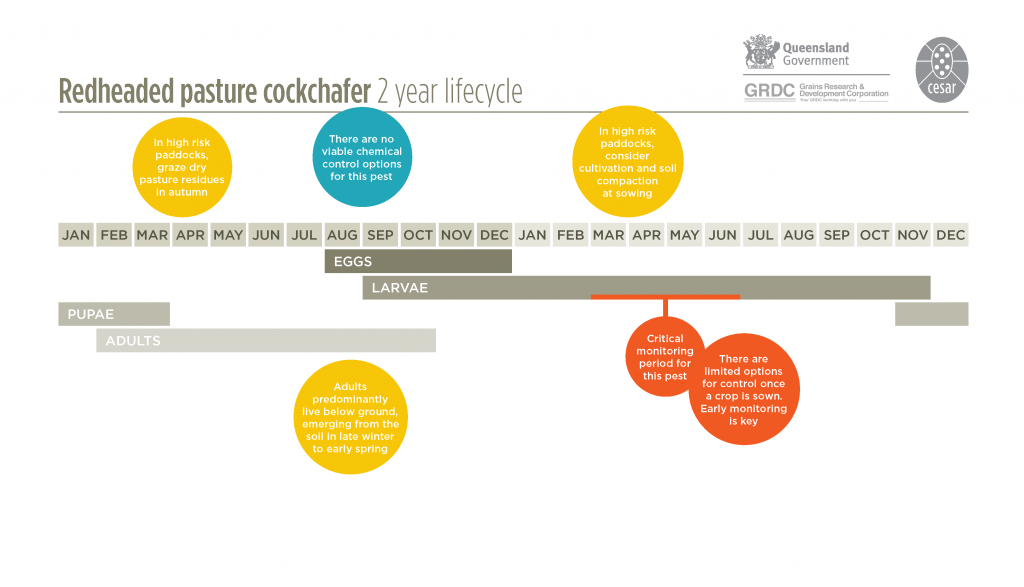

The redheaded pasture cockchafer has a two-year lifecycle. Except for limited crawling on the ground and flight activity of the adults, the entire life cycle occurs below the soil surface. Adult beetles emerge from pupae in the soil during late summer to early autumn, but remain deep in the soil until late winter or early spring. Adults emerge in August to early October, fly locally and lay eggs singly in the soil, preferably in pastures with a dense cover. Eggs hatch after two weeks and larvae remain in the soil, reaching the third and final instar by early autumn. They remain at this stage until early the following summer. When they are about a year old, larvae move deeper into the soil and pupate around December. Next generation adults emerge from the pupae around the end of January, remaining in the soil until early next spring. After a brief period of flight, they return to the pasture and burrow into the soil to mate and lay eggs.

Adults prefer to lay in pastures with a denser cover.

Behaviour Top

As they are primarily root feeders, surface moisture in autumn causes the larvae to move closer to soil surface to feed on roots of emerging seedlings. Final stage larvae cause the most damage to plants when they feed during autumn and winter. Adults do not feed.

Similar to Top

Other scarabs and cockchafers including the African black beetle, the yellowheaded cockchafer and the blackheaded pasture cockchafer. Adults can be confused with dung beetles.

Crops attacked Top

Pastures and occasionally wheat. Ryegrass and pastures with a high clover content are very susceptible to attack. Roots in the top 10 cm of the soil are typically attacked. Deep-rooted perennial plants such as lucerne, cocksfoot and phalaris are less susceptible to damage.

Damage Top

In autumn, increased soil moisture stimulates larvae to move closer to the soil surface to feed on plant roots. Larvae prune or completely sever roots, with damaged plants sometimes dying or showing signs of reduced growth. In severe cases where larval populations are high, pasture can be rolled back like a carpet. High numbers can also result in completely bare patches in the infested paddock from small isolated to very large areas. Damage is typically most serious from March to June. Low soil temperatures over the winter period slow down feeding activity.

Significant pasture losses begin to occur when larvae exceed approximately 70 per m2 in March, and populations have been known to reach 1000 per m2 (Mickan 2008).

Monitor Top

Monitor pastures in late March until June. Inspect susceptible paddocks prior to sowing by digging to a depth of 10-20 cm with a spade and counting the number of larvae present. This should be repeated 10-20 times to get an estimate of larval numbers. Four larvae per spade square is roughly equivalent to 100 larvae per m2.

Economic thresholds Top

There are no economic thresholds established for this pest.

Management options Top

Biological

Birds, parasitic wasps and flies are the most effective natural enemies. Birds prey on larvae and are most valuable after cultivation. Metarhizum spp. are pathogenic fungi that can attack and reduce pasture cockchafer populations. There is an entomopathogenic nematode, Heterorhabitis zealandica, which is used for control in turf and nurseries.

Cultural

Intensively grazing in spring will reduce pasture cover making paddocks less favourable for adult females to lay eggs. If redheaded pasture cockchafers are a continual problem, consider sowing tolerant pasture species such as phalaris, cocksfoot, tall fescue, lucerne or less palatable crops such as oats. Cultivating before May can directly kill larvae while also exposing them to predation. Re-sowing affected areas with a higher seeding rate will assist plant establishment. Delay re-sowing until cockchafer activity ceases. Rolling damp, but not too wet, pastures can be of use by re-establishing contact of the roots with the soil and killing larvae close to the soil surface.

Chemical

There are currently no synthetic insecticides registered for control of redheaded pasture cockchafers. Larvae live underground and the most damaging third instar larva will not be affected by foliar applications of insecticides.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI).

References/Further Reading Top

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: identification and control. CSIRO Publishing. Melbourne. Australia.

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. 2012. I SPY. Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA), the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) and cesar Pty Ltd.

Berg G, Faithfull IG, Powell KS, Bruce RJ, Williams DG, Yen AL 2014. Biology and management of the redheaded pasture cockchafer Adoryphorus couloni (Burmeister) (Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae) in Australia: a review of current knowledge. Austral Entomology 53: 144-158. doi:10.1111/aen.12062

Henry K, Bellati J, Umina P and Wurst M. 2008. Crop Insects: the Ute Guide Southern Grain Belt Edition. Government of South Australia PIRSA and GRDC.

Mickan F. 2008. The Redheaded Pasture Cockchafer, Department of Primary Industries, Melbourne, Victoria, Agnote 1358. http://www.depi.vic.gov.au/agriculture-and-food/pests-diseases-and-weeds/pest-insects-and-mites/the-redheaded-pasture-cockchafer

Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks Water and Environment. 2010. Redheaded pasture cockchafer. Biosecurity fact sheet. http://www.dpiw.tas.gov.au/inter.nsf/Attachments/MCAS-8AD34T/$FILE/redheaded.pdf

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| February 2015 | 1.0 | Bill Kimber (SARDI) | Garry McDonald (cesar) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.