Corn aphid

Rhopalosiphum maidis

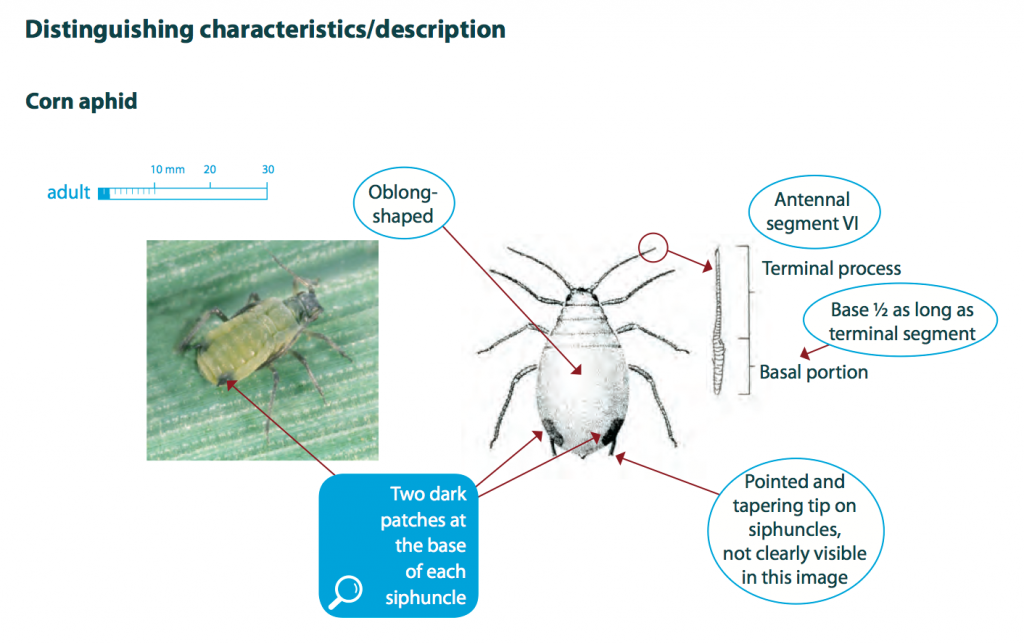

Wingless corn aphid and nymph. Note the lack of a red patch across the siphunculi of the corn aphid. Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

Corn aphids are introduced and a relatively minor pest of cereal crops. They attack all crop stages but most damage occurs when high populations infest cereal heads. Corn aphids are most prevalent in years when there is an early break to the season followed by mild weather conditions in autumn. Corn aphids transmit a number of plant viruses, which can cause significant yield losses.

Occurrence Top

Corn aphids are found worldwide and in all states of Australia. They are most prevalent in years when there is an early break to the season followed by mild weather conditions in autumn. Colonies often develop within the furled emerging leaves of tillers of cereal crops and can be difficult to see.

An introduced species that is a sporadic pest of cereal crops and found in all states of Australia.

Description Top

Aphids are a group of soft-bodied bugs commonly found in a wide range of crops and pastures. Identification of crop aphids is very important when making control decisions. Distinguishing between aphids can sometimes be challenging. It can be easier in the non-winged form but is more difficult with winged aphids.

Corn aphids are light green to dark green, with two darker patches at the base of each cornicle (siphunculi). Adults grow up to 2 mm long, have an oblong-shaped body and antennae that extend to about a third of the body length. The legs and antennae are typically darker in colour.

Nymphs are similar to adults but smaller in size and always wingless, whereas adults may be winged or wingless.

Lifecycle Top

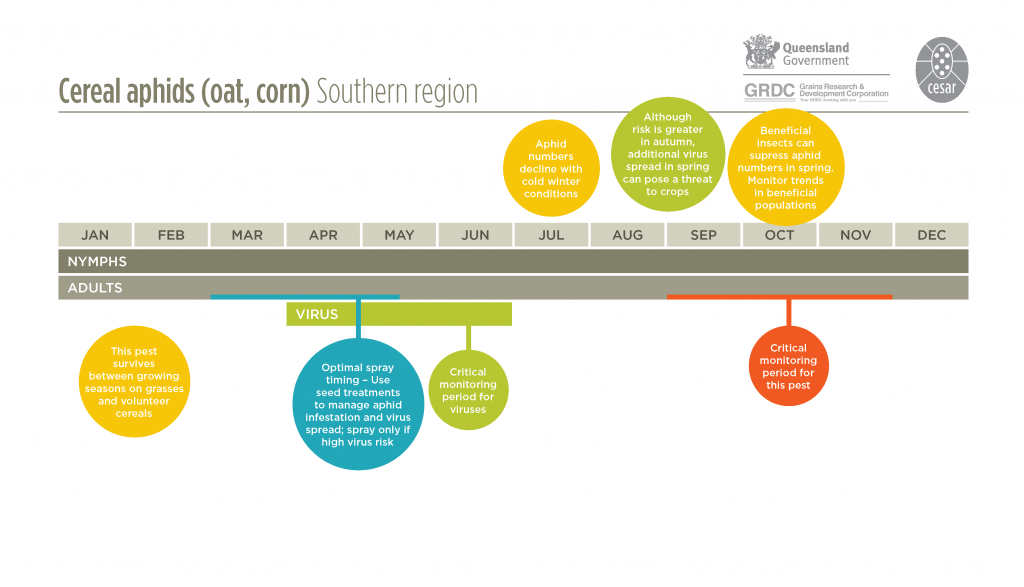

Corn aphids can be found all year round, often persisting on a range of volunteer grasses and self-sown cereals during summer and early autumn. Winged aphids fly into crops from grass weeds, pasture grasses or other cereal crops, and colonies of aphids start to build up within the crop.

Aphids can reproduce both asexually and sexually, however, in Australia, the sexual phase is often lost. Aphids reproduce asexually whereby females give birth to live young.

Temperatures during autumn and spring are optimal for aphid survival and reproduction. During these times, the aphid populations may undergo several generations. Populations peak in late winter and early spring; development rates are particularly favoured when daily maximum temperatures reach 20-25°C.

Young wingless aphid nymphs develop through several growth stages, moulting at each stage into a larger individual. Plants can become sticky with honey-dew excreted by the aphids. When plants become unsuitable or overcrowding occurs, the population produces winged aphids (alates), which can migrate to other plants or crops.

Behaviour Top

Corn aphids can be found all year round and on all cereal crop growth stages. They are often found on the lower portion of the plant, feeding on the undersides of leaves, in the leaf whorl, at the base of tillers and on stems. Colonies generally develop within the furled emerging leaves of tillers and can be difficult to see.

Similar to Top

Other aphids, particularly cereal aphids such as the oat aphid and rose-grain aphid.

Crops attacked Top

Most common on barley, but can also occur on other grasses and cereals including wheat, oats, millet, corn, and sorghum. During summer and early autumn oat aphids may be found on a range of volunteer grasses and self-sown cereals.

Damage Top

Direct feeding damage:

Corn aphids can invade crops at any time between seedling stage and grain fill. Early infestations can cause reduced tillering, stunting and early leaf senescence. Later infestations on leaf sheaths and flag leaves between booting and the milky dough stages can also result in yield losses. In some cases, aphid colonies infest the seed heads and congregate in large numbers. After grain fill, aphid feeding has minimal or no impact on yield. Secretion of honeydew can cause secondary fungal growth, which inhibits photosynthesis and can decrease plant growth.

Visual symptoms of corn aphid attack are often not obvious until close inspection of leaf whorls and sheaths, where dark-coloured masses of aphids may be seen.

Indirect damage (virus transmission):

Corn aphids cause indirect damage by spreading plant viruses. Aphids spread viruses between plants by feeding and probing when they move between plants and paddocks. The ability to transmit particular viruses differs with each aphid species and viruses may be transmitted in a persistent or non-persistent manner. This influences the likelihood of plant infection.

Corn aphids can transmit viruses that contribute to yield losses in crops, including barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV), cauliflower mosaic (CaMV) and turnip mosaic viruses (TuMV). These viruses are not seed-borne. CaMV and TuMV are non-persistent viruses being retained in the aphid mouthparts for less than 4 hours. BYDV infects wheat, barley, oats and grasses. BYDV is a persistent virus. Once an aphid acquires the virus after feeding from the phloem of an infected plant it will continue to transmit the virus to any plant it feeds on for its entire life.

Virus infections are more common in high rainfall cropping zones where virus infected, self-sown cereals and grasses are present, along with large numbers of aphids during the early growth stages of new season crops. BYDV infection decreases grain yield and also causes shrivelled grain. If crops are infected early, BYDV can result in significant losses. In susceptible cereal varieties, where the entire crop is infected by BYDV soon after sowing, yields of wheat, barley and oats can fall by up to 80 %. If the crop is infected late, yield may be reduced by only 10 to 20%.

Corn aphids transmit a number of plant viruses, including barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV). BYDV can result in significant losses if crops are infected early.

Monitor Top

Regular monitoring for cereal aphids should start in late winter and continue through to early spring with more frequent monitoring at the most vulnerable crop stage (stem elongation to late flowering). Aphids will generally move into paddocks from roadsides and damage will first appear on crop edges. Infestations can be patchy.

Inspect crops from the 3-leaf stage onwards by direct visual observations of tillers and plant margins. Check 5 tillers at 6 sites within each paddock. Sampling should occur away from the crop edge to assess the infestation levels within a representative area of the paddock.

Symptoms of virus infections are very variable, from yellowing, reddening and striping of leaves for BYDV, chlorotic ring spots and mottling for CaMV and yellow mosaic patterning and tip necrosis for TuMV. Symptoms of virus infections such as BYDV can be confused with those caused by nutrient deficiencies, waterlogging or other plant stresses that cause. Leaf symptoms differ between wheat, oats and barley. The severity depends on the age of the plant at infection, environmental conditions, the virus present and the cereal variety involved. In barley, BYDV infection causes a characteristic bright yellowing of the leaves (particularly older leaves) and pale yellow stripes between the leaf veins plus chlorotic blotching of young leaves. In some varieties, reddening of leaf tips also develops.

Aphid infestations can be reduced by heavy rain events or sustained frosts. If heavy rain occurs after a decision to spray has been made, but before the insecticide has been applied, check the crop again to determine if treatment is still required.

Economic thresholds Top

Winter cereals:

- WA: In crops with expected yields > 3 t/ha, 50% of tillers with 10-20 aphids per tiller (DAFWA website; Pestweb)

- NSW: More than 15 aphids per tiller on 50% of tillers if the expected yield will exceed 3 t/ha. (Hertel et al. 2013)

- QLD: 90% plants infested and <2 predators per plant (Elder et al. 1992), or 10-15 aphids per tiller (Daniels 2010)

When determining economic thresholds for aphids, it is critical to consider several other factors before making a decision. Most importantly, the current growing conditions and moisture availability should be assessed. Crops that are not moisture stressed have a greater ability to compensate for aphid damage and will generally be able to tolerate far higher infestations than moisture stressed plants before a yield loss occurs.

Thresholds for managing aphids to prevent the incursion of aphid-vectored virus have not been established and will be much lower than any threshold to prevent yield loss via direct feeding.

Management options Top

Biological

There are many effective natural enemies of aphids. Hoverfly larvae, lacewings, ladybird beetles and damsel bugs are known predators that can suppress populations. Aphid parasitic wasps lay eggs inside bodies of aphids and evidence of parasitism is seen as bronze-coloured enlarged aphid ‘mummies’. As mummies develop at the latter stages of wasp development inside the aphid host, it is likely that many more aphids have been parasitized than indicated by the proportion of mummies. Naturally occurring aphid fungal diseases (Pandora neoaphidis and Conidiobolyus obscurus) can also suppress aphid populations.

If the parasitism trend increases over time, there are good prospects that aphid populations will be controlled naturally.

Cultural

Sowing resistant cereal varieties is the most effective method of reducing losses. See crop variety guides for susceptibility ratings.

Control summer and autumn weeds in and around crops, particularly volunteer cereals and grasses, to reduce the availability of alternate hosts between growing seasons.

Where feasible, sow into standing stubble and use a high sowing rate to achieve a dense crop canopy, which will assist in deterring aphid landings.

Delayed sowing avoids the autumn peak of cereal aphid activity and reduces the incidence of BYDV. However, delaying sowing generally reduces yields, and this loss must be balanced against the benefit of lower virus incidences.

Chemical

The use of insecticide seed treatments can delay aphid colonisation and reduce early infestation, aphid feeding and the spread of cereal viruses.

There are several insecticides registered against corn aphids in various crops including cereals. A border spray in autumn/early winter, when aphids begin to move into crops, may provide sufficient control without the need to spray the entire paddock.

Avoid the use of broad-spectrum `insurance` sprays and apply insecticides only after monitoring and distinguishing between aphid species. Consider the populations of beneficial insects before making a decision to spray, particularly in spring when these natural enemies can play a very important role in suppressing aphid populations if left untouched.

Rotating chemical groups and taking advantage of biological control are essential to extend the useful life of the available chemistries.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Sandra Hangartner.

References/Further Reading Top

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: Identification and Control. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. 2012. I SPY Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA), the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) and cesar Pty Ltd.

Blackman RL and Eastop VF. 2000. Aphids on the world’s crops: an identification and information guide. John Wiley and Sons, England.

Coutts BA, Hawkes JR and Jones RAC. 2006. Occurrence of Beet western yellows virus and its aphid vectors in over-summering broad-leafed weeds and volunteer crop plants in the grainbelt region of south-western Australia. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 57: 975–982.

Daniel R. 2010. Aphid management in winter cereals – necessary or just an added cost? Australian Grain. 20 (2).

De Barro PJ. 1992. Karyotypes of cereal aphids in South Australia with special reference to Rhopalosiphum maidis (Fitch) (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Australian Journal of Entomology 31: 333-334.

Edwards OR, Franzmann B, Thackray D, Micic S. 2008. Insecticide resistance and implications for future aphid management in Australia grains and pastures: a review. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 48: 1523-1530.

Elder RJ, Brought EJ, Beavis CHS. 1992. Managing insect s and mites in field crops, forage crops and pastures. QI92004. Queensland Department of Primary Industries. Brisbane.

GRDC. 2010. Cereal aphids fact sheet. http://grdc.com.au/uploads/documents/GRDC_FS_CerealAphids1.pdf

Hertel K, Robers K and Bowden P. 2013. Insect and Mite control in field crops. New South Wales DPI. ISSN 1441-1773.

Miles M. 2009. The research view – winter cereal aphids. Australian Grain 19: 18.

Moran N. 1992. The evolution of aphid life cycles. Annual Review of Entomology 37: 321-348.

Parry HR, Macfadyen S and Kriticos DJ. 2012. The geographical distribution of Yellow dwarf viruses and their aphid vectors in Australian grasslands and wheat. Australasian Plant Pathology Society 41: 375-387.

Valenzuela I, Eastop VF, Ridland PM and Weeks AR. 2009. Molecular and Morphometric Data Indicate a New Species of the Aphid Genus Rhopalosiphum (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 102: 914-924.

Valenzuela, I. and Hoffmann, AA. 2014. Effects of aphid feeding and associated virus injury on grain crops in Australia. Austral Entomology. DOI: 10.1111/aen.12122.

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 2015 | 1.0 | Paul Umina (cesar) and Sandra Hangartner | Alana Govender (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.