Local and migratory armyworm are making their presence felt, with reports coming in from Moama, north-western Victoria and the Mallee area. But this doesn’t necessarily mean they will cause damage to crops.

In this article we will provide information on recent reports and explain why action might not be needed depending on the larvae size and crop stage.

Armyworm refresher

Armyworm is the common name for several species of crop and pasture moth larvae. The native species of armyworm include the common armyworm (Mythimna convecta), the southern armyworm (Persectania ewingii) or the inland armyworm (Persectania dyscrita).

Armyworm moths can be highly migratory and will be more abundant in years when there has been higher rainfall inland or in coastal breeding areas, where source populations are based over autumn and winter. Inland and southern armyworm are the species most likely to be found in Victoria during autumn and winter, as they are relatively cold tolerant, whereas the common armyworm is normally found in NSW over the winter with flights into Victoria occurring during late winter and spring.

Being able to tell the difference between these three armyworm species is generally not critical because their habits, type of damage and control measures are similar.

For more information on armyworm including identification, control and behaviour visit our PestNote.

Recent reports

In the last two weeks we have received reports of armyworm in cereals in Ouyen and Hopetoun, and through the southern Mallee region. Some large common armyworm larvae have also been reported in barley in Moama.

Closer inspection of the images sent showed one of the reports was common armyworm and two were southern armyworm. It’s common to see native species of armyworm in south-eastern Australia at this time of year.

How to know if larvae will cause damage

Crops which are most susceptible to economic damage include barley, oats, rice and grass pastures, but armyworm can also occasionally cause foliage damage or secondary tiller loss in wheat and triticale.

The extent of damage depends on the size of larvae present at vulnerable crop stages; 70% of all food consumed is in the final larval stage (30-40mm).

Defoliation is normally only a risk when armyworm reach very high numbers. While extensive defoliation of tillering and flowering crops is unusual in our region, you can find more information on defoliation rates in this Beat sheet article about extreme defoliation experienced in Queensland in 2019.

Head lopping most frequently occurs during late stages of crop senescence, when the other green material on the plant starts to dry out leaving less palatable food for the larvae at the base of the plant.

Barley is most susceptible to head lopping because it has a relatively thin stem, making it easier for larvae to chew through in comparison to other cereals.

The risk of head lopping is highest when mature caterpillars are present, because armyworm feed more as they reach maturity, and they have bigger jaws for chewing than smaller grubs.

Therefore, the development profile of this pest is key. If small to mid-sized larvae are present as the crop turns, then they are unlikely cause head lopping. Alternatively, if larvae are large enough to pupate before crop senescence, then there won’t be enough grubs left to cause economic loss.

An example from the field

As an example, the grubs found in Moama (shown in the photo above) were around 20mm long, placing them at larval stage 4. Modelling data which incorporates the common armyworm development profile and local climate data predicts that these larvae will pupate by the time the crop starts to senesce. Therefore, the risk of head lopping is very low. These simulations show that factors such as the date that larvae were found, their size, as well as the type and stage of crop are vital when deciding whether intervention is required.

Cesar Australia are currently working on the adaptation of our modelling tool DARABUG for industry use. The app will be used to predict the growth rate and stages of common armyworm and native budworm in relation to the crop stage, to highlight when to focus monitoring efforts and if damage is likely to occur.

If you are interested, we are able to run simulations for common armyworm development and provide information on monitoring dates for your area. Please get in touch for more details.

Monitoring armyworm

Although control of armyworm in south-eastern Australia is rarely needed, it’s important to keep an eye on when large larvae will be present at vulnerable crop growth stages, as explained above.

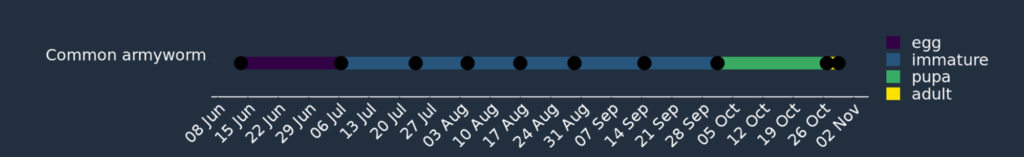

Common armyworm are likely to have migrated into cropping regions from mid winter. Monitoring should occur from August to November, particularly in barley, with the most critical time being 3-4 weeks prior to harvest (although crops should also be monitored during tillering).

Armyworm larvae are active at night, seeking shelter under debris and vegetation on the ground during the day. This means that the best way to monitor is to do a direct ground search along with a sweep net in the evening.

If you find armyworm in your crops, please let us know so we can keep up to date with their numbers in 2021.

Management options

A rule of thumb threshold of 8 – 10 armyworm larvae per m2 in cereals provides a guide for spray decisions during winter and early spring.

When cereal crops (mostly barley or oats) approach ripening and are drying off, the threshold drops to 1 – 3 larvae per m2 due to the risk of head lopping.

Parasitic flies and wasps, predatory beetles and diseases are often effective at suppressing natural populations of native armyworm species.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Leo McGrane and Garry McDonald for contributions to this article, and to the following advisors for their reports: Andrew James (Dodgshun Medlin), Matt Bissett (Independent) and Brad Bennett (Agrivision).