Native budworm (Helicoverpa punctigera) migrate into south-eastern Australia towards the end of winter, so it’s time to start keeping an eye out.

This article is a quick reminder of how to tell the difference between native budworm and corn earworm (Helicoverpa armigera), and how to monitor for flying adults and larvae in grain crops.

Native budworm

As the common name suggests, Helicoverpa punctigera is a native moth that is common and widely distributed throughout Australia.

It is highly migratory, and populations normally build up in native vegetation in inland Australia over winter before moving into crops in south-eastern Australia in late winter to spring.

While native budworm can sometimes reach large numbers, there are well established economic thresholds and a number of effective control methods, including natural enemies which can result in high mortality for early larval stages.

For more information on native budworm management and economic thresholds, see PestNotes.

Distinguishing between Helicoverpa species

Corn earworm (Helicoverpa armigera) and native budworm (Helicoverpa punctigera) both are major agricultural pests that somewhat overlap in their distribution and host range e.g. pulses and canola.

However, you can sometimes distinguish between the two species depending on where and when they are found. For example, if found in cereals, it will likely be corn earworm, as native budworm is largely restricted to broadleaf hosts and is not found on grass or cereal crops (e.g. wheat, barley, sorghum or maize).

As for timing, native budworm moths are migratory and will arrive in south-eastern Australia over the August to October period. Corn earworm on the other hand, generally arises from local populations that survive over winter as pupae, emerging with warmer spring temperatures. So you won’t normally see corn earworm occurring until October to mid-November.

Corn earworm continue to be observed through to the new year; and can cause problems in very late season wheat, maize/sweetcorn and in summer pulses (in southern NSW) like mung beans and soy beans.

For more information on corn earworm, see PestNotes.

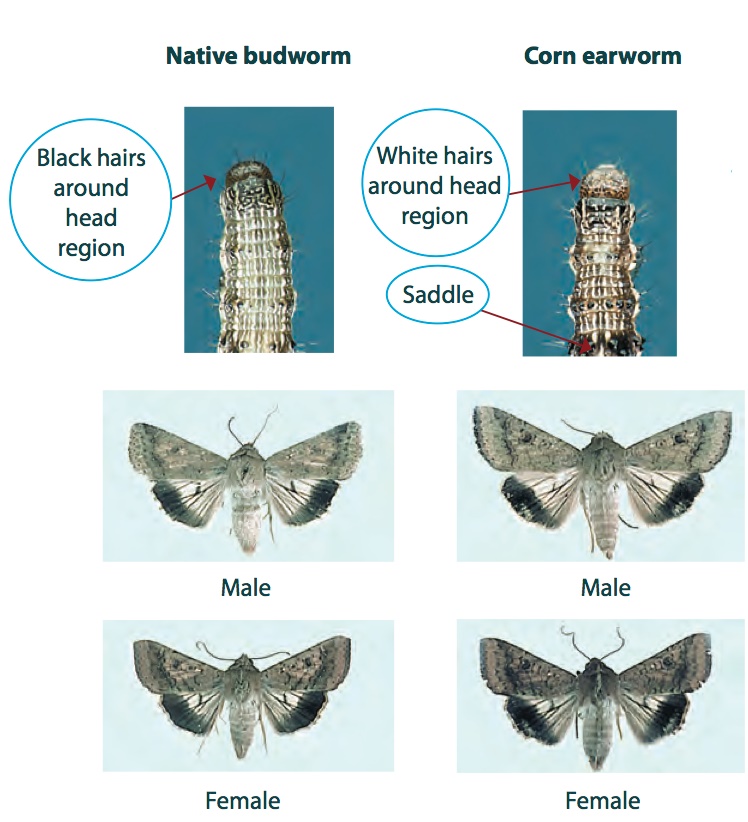

Morphologically the two species are very similar, with the main difference being that native budworm caterpillars have black hairs in the head region, whereas the corn earworm has white hairs and a dark saddle pattern. It is important to note that morphological indicators are not always reliable, and they are often only visible on larger caterpillars (both species are best controlled while they are small – up to 7 mm in length).

The most important difference between the two species is that corn earworm has developed resistance to insecticides and native budworm has not. This means it is important to distinguish between the two before spray decisions are made, and if you suspect the pest is corn earworm check out its resistance management strategy.

If you would like help identifying moth larvae or adults, you can submit a photo or a live sample to our pest identification service.

Monitoring

The arrival of native budworm moths in agricultural regions can be monitored with pheromone traps. These traps use a female sex scent lure that attracts male moths of the native budworm.

Lures and bucket traps can be purchased online.

Early warning of the arrival the adults provides an indication of when egg-laying commences, and when crop monitoring should start.

Larvae generally hatch 7-14 days after eggs are laid, so once adults are detected, monitoring for larvae can be planned.

When sweep netting, take a minimum of 5 sets of 10 sweeps across the crop and calculate the average number of larvae per 10 sweeps. Each sweep should involve moving the net through the crop in an arc of approximately 180°.

Sweep netting doesn’t work well in taller or rigid crops (e.g. faba beans), so we recommend a beat sheet instead.

Native budworm trapping network

Although trapping numbers were low in September last year, the size of migrating moth populations varies considerably from year to year. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that the moths are moving into south-eastern Australia gradually earlier each year.

Each year, with the help of agronomists and growers, Cesar Australia deploys pheromone traps in pulses and canola in locations in the Victorian Wimmera and Mallee, and the Murray and Central West regions of NSW.

We report the numbers of moths trapped via PestFacts so that growers and advisors can be alerted to the movement of adult moths into their area.

As the season progresses, we will also be monitoring and tracking reports of native budworm larvae. If you suspect you have seen any, please send in a report.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to our trapping network participants: Adam Dellwo (Elders), Alise Riley (Vickery Bros.), Andrew Rice (Aspire Agri), Ben Cameron, Brad Bennett (AGRIvision), Bruce Larcombe (Larcombe Agronomy), Damian Jones (Irrigated cropping council), Darren Jones (CropSmart), David White (Delta Ag.), George Hepburn (Tyler’s Rural), Jim Cronin (Nutrien Ag), Max Ridley (Nutrien Ag), Rob Fox (Fox and Miles) and Shayn Healey (Crop-Rite). Additional thanks to Garry McDonald for contributions to this article.

Cover image: Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia