Valentine’s Day usually celebrates new love, grand gestures and dramatic romance. But some of the most remarkable partnerships on Earth are far smaller, yet far more enduring.

Long before flowers and chocolates, there were endosymbionts.

Endosymbionts are organisms that live inside insects (their host). The term literally means “living together inside.” And in many cases, these relationships are not just a Valentine fling. They are stable, tightly integrated partnerships that have persisted for millions of years.

What exactly is an endosymbiont?

Most endosymbionts are bacteria that live within the cells of an insect. The insect provides shelter and nutrients. In return, the endosymbiont performs functions the insect cannot do alone.

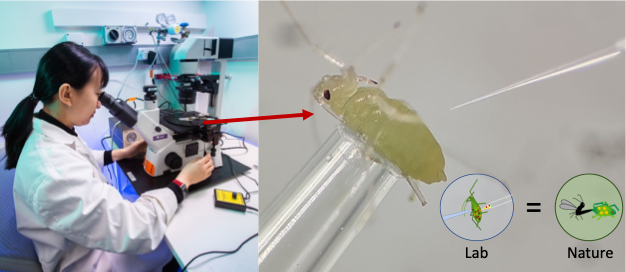

Some of these functions are essential. Aphids, for instance, feed on plant sap, a diet rich in sugars but deficient in key amino acids. Their primary endosymbiont, Buchnera, makes those missing nutrients for it. Without Buchnera, aphids cannot survive or reproduce normally. The relationship is obligate for both partners: the aphid depends on the endosymbiont for nutrition, and the endosymbiont cannot live outside the aphid.

That is not a short-term arrangement. Genetic evidence suggests this partnership has been stable for over 100 million years.

Not all relationships are equal

Endosymbiotic relationships exist along a spectrum.

- Obligate – both host and symbiont depend entirely on each other for survival (e.g. aphids and Buchnera).

- Facultative – the host can survive without them, but gains new traits when they are present.

In many agricultural pests, facultative endosymbionts can influence traits such as heat tolerance, resistance to predators, or susceptibility to insecticides. These relationships are more flexible and dynamic than the deeply integrated obligate endosymbiont symbioses, but they can still be stable across generations.

When Partnerships Go Viral

Most endosymbionts are inherited vertically, passed directly from mother to offspring. That tight maternal transmission is what makes many of these relationships so stable across generations.

Some endosymbionts can also move horizontally between individuals. For example, insects feeding on the same plant can exchange endosymbionts, allowing them to spread within a population rather than just down family lines.

And it doesn’t stop there. In controlled laboratory settings, we can now deliberately introduce specific endosymbionts into aphids. That means these partnerships are not only inherited or naturally acquired, they can also be engineered.

Why this matters in agriculture

The best-known example of endosymbiont manipulation outside agriculture is Wolbachia in mosquitoes, where endosymbionts transferred to mosquitoes have been used to suppress disease transmission. Now, there is growing interest globally in whether endosymbionts can be leveraged in pest management.

Because they affect so many factors of insect biology, endosymbionts can shape pest population dynamics. Some endosymbionts may change how many offspring an insect has, potentially reducing pest pressure. Others might decrease their overall fitness, meaning they’re less likely to survive. Some endosymbionts even appear to alter an insect’s ability to acquire or transmit plant viruses, potentially influencing the spread of disease within crops.

In other words, they can shift how a pest performs in the field and how it responds to control strategies.

Researchers are actively exploring ways to introduce or manipulate endosymbionts in pest species, including through the Australian Grains and Horticulture Pest Innovation Program trials, to better understand how these microbes influence pest biology. While still experimental, this work is helping identify potential approaches to support more targeted and sustainable pest management.

A different kind of long-term commitment

On a day associated with fleeting symbols of affection, endosymbionts remind us that some relationships are measured not in weeks or years, but in geological time.

They are invisible, intracellular and often overlooked. Yet endosymbionts underpin insect nutrition, influence pest ecology, and may present major opportunities for sustainable pest control.

Few partnerships are as stable, or as consequential, as that of endosymbionts and insects.

Acknowledgement

This research is being undertaken as part of the Australian Grains and Horticulture Pest Innovation Program (AGHPIP). AGHPIP is a collaboration between the Pest & Environmental Adaptation Research Group at the University of Melbourne and Cesar Australia. The program is a co-investment by the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC), Hort Innovation, and the University of Melbourne, together with in-kind contributions from all program partners.

Cover image: Aphids of different colours due to endosymbiont infections. Photo courtesy of Perran Ross (PEARG).