Eastern false wireworm

Pterohelaeus spp.

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

Eastern false wireworm is an occasional pest of cereal crops in eastern Australia. They are similar to although often larger than other false wireworms, including the bronzed field beetle and the vegetable beetle. Larvae have cylindrical elongated bodies that range in colour from creamy-tan to yellow-orange.

Stubble retention and minimum tillage are thought to contribute to population build-up.

Occurrence Top

Known to occur in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria.

Description Top

There are numerous species of Pterohelaeus, although P. darlingensis and P. alternatus are most common in cropping systems. Technically, P. darlingensis is the species mostly referred to as the eastern false wireworm.

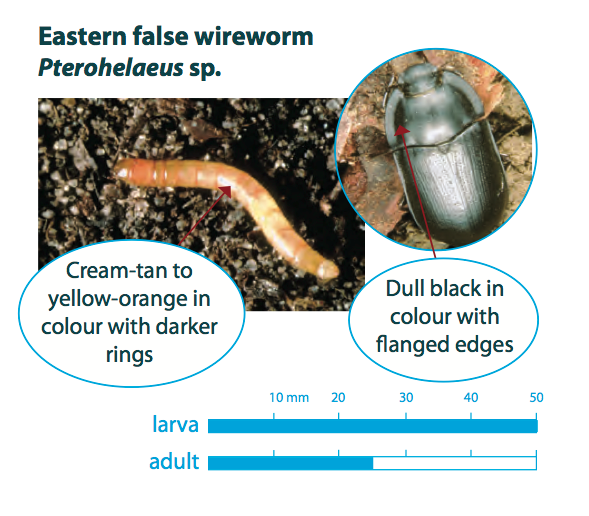

Eastern false wireworm larvae are typically large and range in colour from cream-tan to yellow-orange. They have a hardened cylindrical body with a darker ring around each segment, giving the appearance of bands. Fully grown larvae can reach about 50 mm in length. They have 6 legs and a rounded head. Eastern false wireworm larvae do not have obvious upturned spines on the end of the last segment like some other false wireworms. Adult beetles are dull black in colour and approximately 25 mm long. They are sometimes referred to as ‘pie-dish beetles’ due to their body shape and the broad flanges (rims) around the edges of their body.

Lifecycle Top

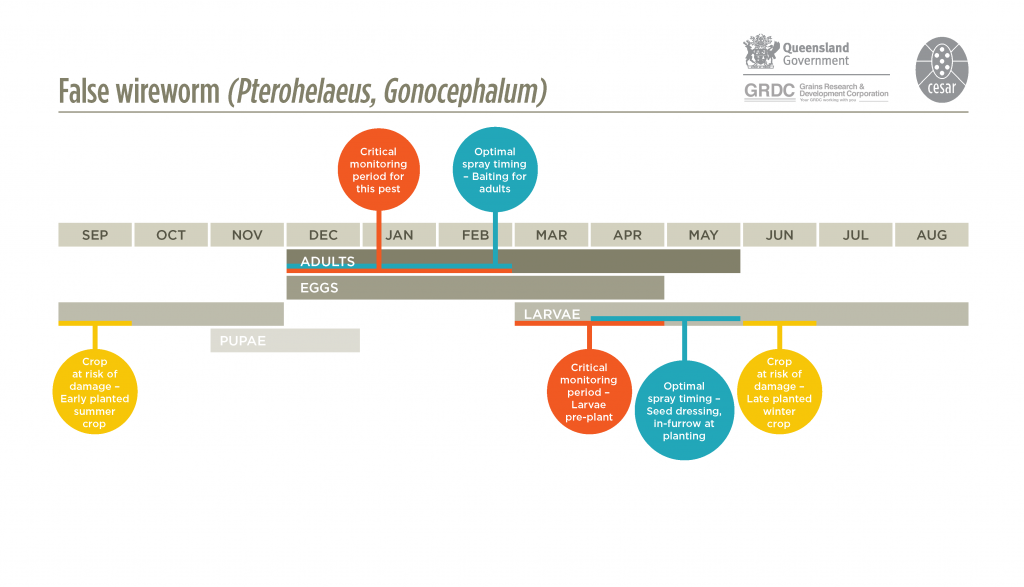

Adults lay eggs in summer-autumn in the soil near crop residues or organic matter. Eggs are laid singly under dried stubble and hatch 7-14 days later and larvae are found in loose clusters within the top 10-20 mm of moist soil. Larvae develop over autumn, winter and spring, and when fully grown, burrow deeper where they pupate. Adults emerge in late spring or early summer. Eastern false wireworms may have two generations per year under ideal conditions, however, soil temperature and soil moisture are likely to prevent this in most regions.

Behaviour Top

False wireworms move through the soil to remain just above the level of soil moisture. Larvae feed on grain, germinating seed and subsequently bore into underground stems of cereal plants causing withering and death. They can be particularly prominent after a pasture phases of 4-5 years. The crop feeding causes thinned or bare patches in the paddock. Where two generations occur in a year, larvae are active between autumn and spring before adults of this generation aestivate during spring and summer. The summer generation larvae are active during spring and summer with adults aestivating in autumn and winter.

False wireworms can survive through continuous cropping by feeding on stubble mulch.

Similar to Top

Adults are similar to other false wireworms, including the bronzed field beetle and the vegetable beetle. Larvae are similar to vegetable beetle larvae and true wireworms. Adults may also be confused with the predatory carabid beetles.

Crops attacked Top

Predominantly cereals, but also may be an occasional pest of canola.

Damage Top

Adult beetles and larvae may damage plants by chewing stems at or below ground level, causing them to fall over or wither while standing. Larvae can also attack plant roots and germinating seeds, causing a patchy germination of the crop. Generally larvae will only attack germinating crops if the soil is dry and if there is insufficient soil moisture and organic matter from which to feed.

Monitor Top

Check paddocks prior to sowing by digging to a depth that includes the moist soil layer where larvae will be present. Repeat this process a number of times across the paddock to get a representative sample. Paddocks coming out of long-term pasture are at most risk.

Alternatively, germinating seed baits can be used immediately following the autumn break. Soak wheat seed in water to initiate germination. Then bury several seeds under 1 cm of soil at each corner of a 5 x 5 m square grid, and give the immediate area a water with 1-2 litres. Immediately after seedling emergence, re-visit the bait site, dig up the plants and count the number of larvae present. Repeat this at 5 locations per 100 ha to obtain an estimate of numbers. For a brief demonstration of a comparable process in summer crops, see this link.

Economic thresholds Top

In cereals, treatment may be required if there are more than 10 larvae per m2 (Bailey 2007). If using germinating seed baits, treatment is required if more than 25 wireworm larvae are found in 20 baits (Miles and Lloyd 2007).

Management options Top

Biological

Carabid beetles are known predators of soil-dwelling insects including eastern false wireworm larvae, however, they are usually not present in high enough numbers to effectively suppress large pest populations. Other natural enemies are likely to include spiders, native earwigs and other predatory beetles.

Fungal diseases caused by Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana can attack false wireworm populations but their effectiveness in the field is not fully understood (Allsopp 1980).

Cultural

Stubble retention is thought to contribute to the build-up of eastern false wireworm populations. Removal of trash is an effective management strategy. Methods of stubble removal may include cutting, baling, grazing or burning. Cultivation before seeding may reduce the survival rate of larvae. Use press wheels at sowing, which are set at 2-4 kg per cm width after planting rain or 4-8 kg per cm in dry soil. Consider sowing a pulse crop if high populations of eastern false wireworms are present.

Chemical

Chlorpyrifos is registered as a foliar spray against false wireworms in certain broadacre crops in some states. Several insecticide seed treatments are also registered for false wireworm control in certain broadacre crops in some states. See the APVMA website for current chemical options.

False wireworm cannot be controlled by applying chemicals after sowing; monitoring before sowing is recommended.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI).

Richard Lloyd and Tonia Grundy (Queensland Department of Agriculture) produced the YouTube video.

References/Further Reading Top

Allsopp PG. 1979. False wireworms in southern and central Queensland. Queensland Agricultural Journal 105,276-8.

Allsopp, PG. 1980. The biology of false wireworms and their adults (soil-inhabiting Tenebrionidae) (Coleoptera): a review. Bulletin of Entomological Research 70, 343–379.

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: Identification and Control. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. (2012). I SPY. Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA), the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) and cesar Pty Ltd.

Gu H, Fitt GP and Baker GH. 2007. Invertebrate pests of canola and their management in Australia: a review. Australian Journal of Entomology 46, 231–243.

McDonald G. 1995. Wireworms and False Wireworms in Field Crops. Agriculture Notes (Ag0411). Department of Primary Industries, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Miles M and Lloyd R. 2010. False wireworm. Soil insects in Queensland. https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/plants/field-crops-and-pastures/broadacre-field-crops/integrated-pest-management/a-z-insect-pest-list/soil-insects/false-wireworm

Roberts LN. 1993. Population dynamics of false wireworms (Gonocephalum macleayi, Pterohelaeus alternatus, P. darlingensis) and development of an integrated pest management program in central Queensland field crops: a review. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 33, 953–962.

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| January 2015 | 1.0 | Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI) | Alana Govender (cesar) and Garry McDonald (cesar) |

| March 2016 | 1.1 | Garry McDonald (cesar) | Bill Kimber (SARDI) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.