Blackheaded pasture cockchafer

Acrossidius tasmaniae

Other common names

Scarab

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

A native beetle that is a pest of pastures and cereals. The larvae have a typically dark brown-black head capsule and live in the soil, occasionally coming above ground to feed. Third instar larvae cause the most feeding damage to pastures and crops. Once larvae mature, they will stop feeding and stay below ground. Unlike other cockchafers, foliar insecticides can be used to control this pest.

Foliar application of insecticides is effective on young larvae as they feed on green plant material.

Occurrence Top

The blackheaded pasture cockchafer is a native insect of south-eastern Australia. The larvae are a pest of pastures and cereal crops in parts of Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and New South Wales. They are most problematic in areas where the annual rainfall exceeds about 480 mm.

Description Top

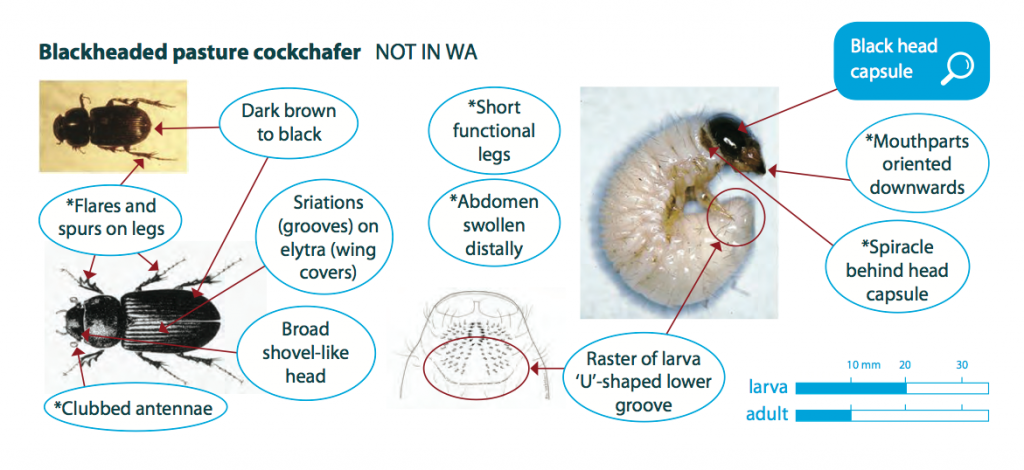

Larvae are white or greyish-white in colour with a hard, dark brown to black head capsule. They have soft bodies, have six legs and are grub like. Fully-grown larvae are 15 to 20 mm long and larvae tend to curl into a ‘C’-shape when exposed or handled.

Blackheaded pasture cockchafer adults (beetles) are approximately 10 mm long, dark brown to black in colour. They have long fine legs and a shovel like head with clubbed antennae. Distinguishing between most species of Scarabaeidae ‘C’-shaped larvae is difficult and requires a microscope to compare hair structure. As blackheaded pasture cockchafer is a foliage feeder, the presence of green material which they take into their tunnels for 7-10 days is a good indicator of this species.

Lifecycle Top

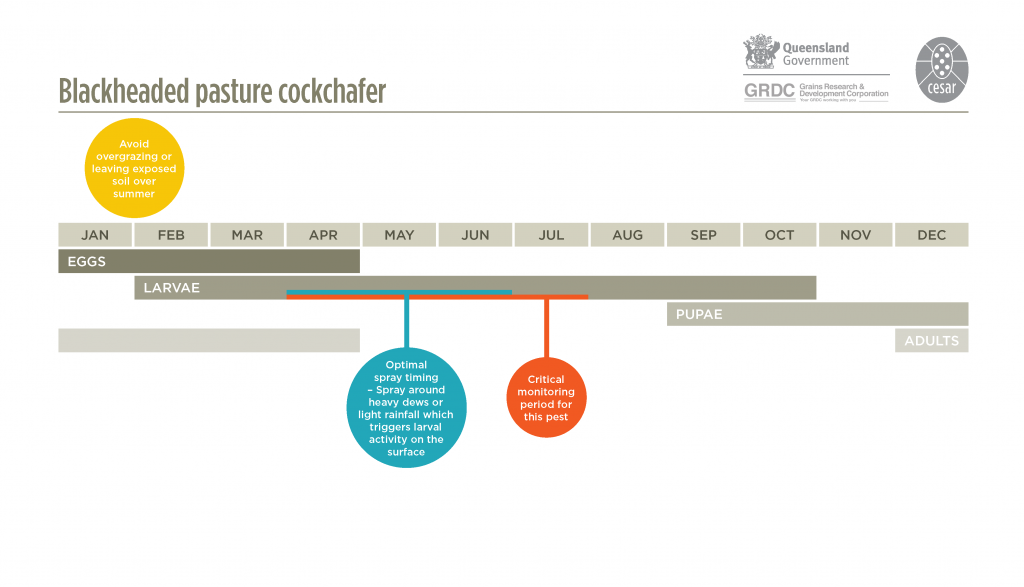

They have a one-year lifecycle. Adult beetles emerge from the soil in mid to late summer (late January to March) and live for several weeks. Flights are common at dusk on calm, warm evenings and the cockchafers are attracted to lights on hot, still summer evenings. Adult females are attracted to sparse pastures – caused by heavy grazing or cutting for hay – to lay their eggs. They will lay eggs on bare earth. Eggs are laid between January-February and hatch after 3-4 weeks. Larvae emerge and initially live on humus in soil, before moving to feed on foliage above ground. Third instar larvae cause the most feeding damage to pastures and crops. Growth rate of larvae depends on the number of days of rainfall in autumn and winter. Pupation occurs from early to late spring.

Behaviour Top

Blackheaded pasture cockchafer larvae live in underground tunnels, and rainfall and heavy dews trigger the larvae to leave the tunnels and move onto the surface to feed. Larval activity results in small mounds of dirt surrounding tunnels on the soil surface.

Similar to Top

All other ‘C’-shaped scarab and cockchafer larvae. However, blackheaded pasture cockchafer is the only-surface feeding scarab larva. Adults can be confused with dung beetles.

Crops attacked Top

Pastures and cereals.

Damage Top

Blackheaded pasture cockchafer attacks young seedlings, severing leaves and causing defoliation. Leaves may be observed pulled into soil tunnels. While most damage occurs to pastures during late winter and in cereals at the seedling stage, feeding damage can cause bare patches within paddocks in late autumn and early winter. The presence of tunnels in heavily infested areas may make the soil feel spongy underfoot.

Monitor Top

Crops sown into paddocks that previously were pasture are vulnerable to attack especially where there was minimal plant cover during summer. Monitor pastures and cereal crops from May to late June. Inspect susceptible paddocks prior to sowing by digging to a depth of 10-20 cm with a spade and counting the number of larvae present. This should be repeated 10-20 times to get an estimate of larval numbers. Estimate the density to a square metre equivalent to compare with the current economic threshold.

Economic thresholds Top

30 larvae per m2 for pastures and cereals (State of Queensland, 2016)

Management options Top

Biological

Birds, parasitic wasps and flies are the most effective natural enemies. Birds prey on larvae and are most valuable after cultivation. Pathogenic fungi Metarhizum spp. and Cordyceps gunnii attack pasture cockchafers and can have a devastating influence in local populations.

Cultural

Cultivating before sowing or sowing with soil disturbance will expose larvae to predation. Avoid overgrazing pastures during late spring and early summer as these areas will be favored for egg-laying by adult females. If possible, maintain pasture cover at 400-600 kg DM/ha or 5 cm in height. If cockchafers are a continual problem, consider sowing tolerant pasture species such as phalaris and cocksfoot.

Chemical

There are several foliar insecticides registered for blackheaded pasture cockchafer. These are effective against larvae that are actively feeding above the surface and should be applied just prior to rainfall or dews. Once larvae mature, they will stop feeding and stay below ground. For best results insecticide sprays should be applied before June.

Foliar insecticides are particularly effective on young larvae before they begin voraciously feeding on green plant material.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI).

References/Further Reading Top

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: identification and control. CSIRO Publishing. Melbourne. Australia.

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. 2012. I SPY. Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA), the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) and cesar Pty Ltd.

Henry K, Bellati J, Umina P and Wurst M. 2008. Crop insects: the Ute Guide, Southern Grain Belt Edition. Government of South Australia PIRSA and GRDC.

Mickan F. 2008. The blackheaded pasture cockchafer. Victorian Department of Environment and Primary Industries. http://www.depi.vic.gov.au/agriculture-and-food/pests-diseases-and-weeds/pest-insects-and-mites/the-blackheaded-pasture-cockchafer

McQuillan PB, Ireson J, Hill L & Young C. 2007. Tasmanian Pasture and Forage Pests. Identification, Biology and Control. Department of Primary Industries and Water, Kings Meadows, Tasmania, Australia.

State of Queensland. 2016. Blackheaded pasture cockchafer. IPM guidelines for grains. https://ipmguidelinesforgrains.com.au/pests/soil-insects/blackheaded-cockchafer/

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| January 2015 | 1.0 | Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI) | Garry McDonald (cesar) |

| February 2015 | 1.1 | Updates by Julia Severi (cesar) | Rebecca Hamdorf (SARDI) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.