Pea aphid

Acyrthosiphon pisum

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

Pea aphids are considered a minor and irregular pest of lucerne, some pulse crops and pasture legumes. They are large in size, with distinctive dark knee joints and antennal segments. Their body colour is variable and they are widely distributed across Australia.

Occurrence Top

A native of Europe, the pea aphid is widespread in Australia and has been recorded in Tasmania, Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia.

Description Top

Aphids are a group of soft-bodied bugs commonly found in a wide range of crops and pastures. Identification of crop aphids is very important when making control decisions. Distinguishing between aphids can sometimes be challenging. It can be easier in the non-winged form but is more difficult with winged aphids.

Adult pea aphids grow up to 4 mm long. They have red eyes and the body colour varies between green, yellow, pink and red. Pea aphids have blackish knee joints and dark joints along the antennal segments. They have long cornicles and a long cauda (tail). Adult aphids may be wingless or winged. Nymphs are similar to adults but are smaller in size and do not have wings.

Lifecycle Top

Winged aphids fly into crops from broad leaf weeds, pasture legumes and vetch, and colonies of aphids start to build up within the crop. Aphids can reproduce both asexually and sexually, however in Australia, the sexual phase is often lost. Aphids reproduce asexually whereby females give birth to live young, which are often referred to as clones.

Nymphs, which do not have wings, go through several growth stages, moulting at each stage into a larger individual. Mature females can produce many generations during the growing season. Development rates are dependent on temperature and either cooler, or extremely hot temperatures slow development.

Behaviour Top

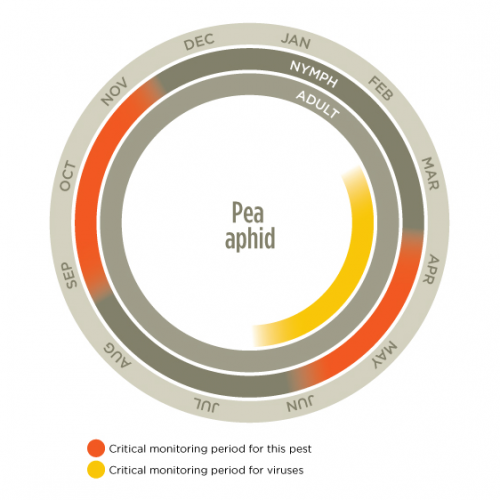

Pea aphids are common in spring, but also active in autumn and winter. Pea aphids form colonies in great densities during favourable conditions. Highest densities are often found in lucerne paddocks.

Similar to Top

Other aphids, in particular the green peach aphid and bluegreen aphid.

Crops attacked Top

Faba beans, field peas, lucerne, vetch, clover, and other leguminous grasses.

Damage Top

Direct feeding damage:

Pea aphids feed on the upper leaves, stems and terminal buds of their host plants. Heavy infestations can result in various types of damage to plants including deformed leaves, wilting and yellowing, stunted plant growth, leaf curling and leaf drop, and reduced dry matter production. In lucerne, the tops of infested plants have small leaves and spindly stems. Secretion of honeydew can cause secondary fungal growth, which inhibits photosynthesis and can decrease plant growth. In pulse crops, aphid feeding damage (in the absence of virus infection) can result in yield losses of up to 90% in susceptible varieties, and up to 30% in varieties with intermediate resistance.

Indirect damage (virus transmission):

Pea aphids cause indirect damage by spreading plant viruses. Aphids spread viruses between plants by feeding and probing as they move between plants and paddocks.

Pea aphids transmit several important plant viruses including cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV), alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) and pea seed-borne mosaic virus (PSbMV).

Pea aphids can transmit important plant virus diseases including cucumber mosaic virus and bean yellow mosaic virus and alfalfa mosaic virus

Monitor Top

Pea aphids are most prominent during spring. Regularly monitor vulnerable crops during bud formation to late flowering. Aphids will generally move into paddocks from roadsides and damage will first appear on crop edges. Aphid distribution may be patchy, so monitoring should include at least 5 sampling points over the paddock. Inspect at least 20 plants at each sampling point. Search for aphids by looking at the youngest inflorescence of each plant. Look for clusters of aphids or symptoms of leaf yellowing or leaf-curling.

Aphid infestations can be reduced by heavy rain events or sustained frosts. If heavy rain occurs after a decision to spray has been made, but before the insecticide has been applied, check the crop again to determine if treatment is still required.

Economic thresholds Top

Lupins:

• WA: If more than 30% of growing tips are infested with clusters of 30 or more aphids

• NSW: Treat at appearance of clusters on flowering plants

Faba beans:

• VIC: 10% of plants infested

Management options Top

Biological

There are many effective natural enemies of aphids. Hoverfly larvae, lacewings, ladybird beetles and damsel bugs are known predators that can suppress populations. Aphid parasitic wasps lay eggs inside bodies of aphids and evidence of parasitism is seen as bronze-coloured enlarged aphid ‘mummies’. As mummies develop at the latter stages of wasp development inside the aphid host, it is likely that many more aphids have been parasitised than indicated by the proportion of mummies. Naturally occurring aphid fungal diseases (Pandora neoaphidis and Conidiobolyus obscurus) can also affect aphid populations.

Cultural

Sow crops early to enable plants to begin flowering before aphid numbers peak in spring. Control summer and autumn weeds in and around crops to reduce the availability of alternate hosts between growing seasons. Use a high sowing rate to achieve a dense crop canopy, which will assist in deterring aphid landings.

Chemical

There are several insecticides registered against pea aphids. Pirimicarb provides effective control and has little impact on beneficial insects compared with broad-spectrum chemicals. A border spray in autumn/early winter, when aphids begin to move into crops, may provide sufficient control without the need to spray the entire paddock.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI).

References/Further Reading Top

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: Identification and Control. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. 2012. I SPY Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA), the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) and cesar Pty Ltd.

Blackman RL and Eastop VF. 2000. Aphids on the world’s crops: an identification and information guide. John Wiley and Sons, England.

Henry K, Bellati J, Umina P and Wurst M. 2008. Crop Insects: the Ute Guide Southern Grain Belt Edition. Government of South Australia PIRSA and GRDC.

Moran N. 1992. The evolution of aphid life cycles. Annual Review of Entomology 37: 321-348.

Valenzuela I and Hoffmann AA. 2015. Effects of aphid feeding and associated virus injury on grain crops in Australia. Austral Entomology. DOI: 10.1111/aen.12122.

Walsh T and Edwards O. 2009. Environmental assessment report for the live import of the Pea Aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. CSIRO Entomology Canberra.

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 2015 | 1.0 | Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI) | Alana Govender (cesar) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.