We have recently received reports of large numbers of Redheaded pasture cockchafer on some farms in Victoria. Here we provide information on this pest and discuss the importance of long-term strategies for its management.

Redheaded pasture cockchafer

Redheaded pasture cockchafer, Adoryphorus coulonii, is an agricultural pest native to south-eastern Australia. It can be found in south-west and central Victoria, northern Tasmania, south-eastern South Australia and the southern tablelands of New South Wales.

Redheaded pasture cockchafer larvae are greyish-white to cream in colour with a hard red-brown head capsule. Fully-grown larvae are up to 30 mm long and curl into a ‘C‘-shape. Adult beetles are reddish-brown to black in colour, and are approximately 15 mm long and 8 mm wide. They have flares/spurs on their legs and clubbed antennae.

There are other cockchafer pests present in south-eastern Australia, including the blackheaded pasture cockchafer, yellowheaded cockchafer, African black beetle and the little known Argentinian scarab (Cyclocephala signaticollis), which was found in high numbers in lucerne in Central West NSW last year.

Despite their common names, correct identification relies on more than just head colour. For more information of scarab and cockchafer identification see our 2020 PestFacts article.

The readheaded pasture cockchafer can affect a range of annual and perennial grasses and clover. Non-tussock grasses are most vulnerable because of their shallow root structure. In rare circumstances damage can occur to cereal crops if sowing occurs directly after conversion from pasture.

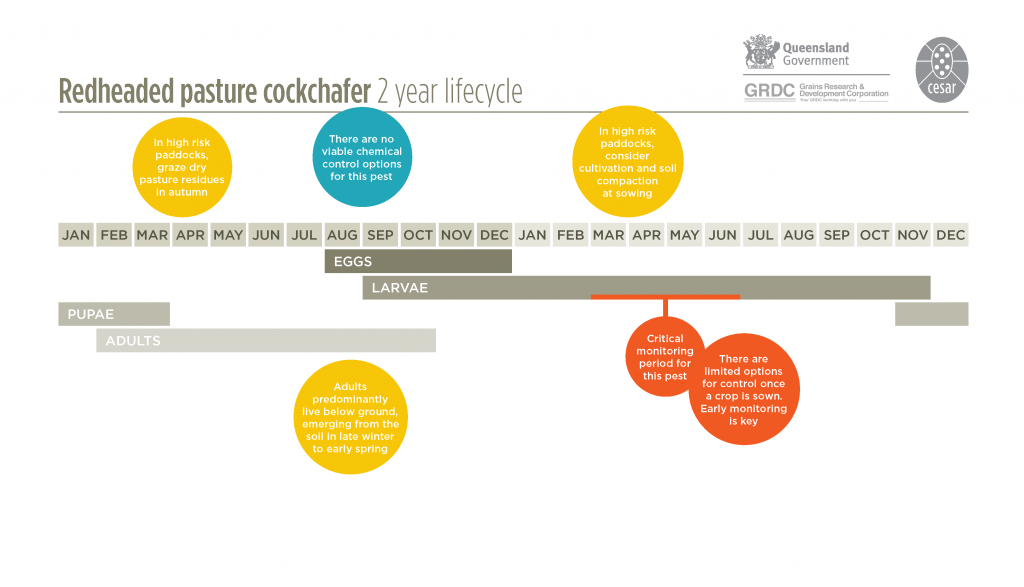

The larvae of the redheaded pasture cockchafer are most active in their third instar stage, which they reach in late summer-early autumn. Late instars will reduce feeding activity over winter before becoming more active again from August. They will then continue feeding until they pupate and become adults in early summer (although adults remain underground without feeding for another 6-9 months before emerging).

Distribution in south-east Australia and historical outbreaks

The redheaded pasture cockchafer is a sporadic pest and is normally only problematic where annual rainfall reaches between 500-800mm and in areas of lighter sandy loam soils (although they can be found in wetter areas such as South Gippsland).

In Victoria it has only been identified as a significant pest in southern Victoria and areas in Western, Central and Gippsland districts, with a few isolated reports in the north west (Mildura and Ouyen).

In NSW it has previously been found in the Southern Tablelands with a few reports from South West Slopes and Central Tablelands.

Outbreaks were traditionally associated with poorly managed pastures, but in more recent years populations have been increasing in well-managed systems. They have also been found in soils that were not thought to be good habitat for this species, presumably due to the higher organic load found in these systems, which can support cockchafer feeding.

In the past, an outbreak in Tasmania in 1993 reached 1100 larvae/m2 with extensive damage to pasture. In 1958 the highest density of 64 larvae per spade cut (2064 larvae/m2) was recorded at Birregurra, Victoria.

Recent Reports

In the last week we have received two reports of redheaded pasture cockchafer damage to ryegrass and clover paddocks in MacArthur and Strathbogie. In both instances the feedbase was severely affected. For the MacArthur region in particular, reporting indicated that there are a number of producers affected this year.

The density of cockchafers in Strathbogie was reported to be ~10/spade (relatively low compared to historical outbreaks). No densities were recorded in Macarthur but when the grass was rolled back in damaged areas there were high numbers of the redheaded cockchafers in the soil.

Both reports indicated that the pests are causing a significant reduction in the availability of feed in the paddocks with the severity of damage caused being likened to conditions experienced during a drought year. The farmers/advisors noticed that the cockchafers were causing the pasture to roll back like a carpet. This occurs when root systems are severed at a shallow depth and can reduce pasture productivity due to plant stress.

In Strathbogie it was noted that crows have begun to fly into the paddock in large numbers to feed on the cockchafers. Flocks of birds feeding can be an initial indicator of a cockchafer infestation, and while the birds do act as biological control agents, their activity digging up the grubs can cause further damage to an already vulnerable pasture.

In circumstances such as these, where numbers are already high, one approach is to leave the paddock to fallow over winter to protect the remaining sward and allow it to re-establish root growth, or when possible, to renovate the pasture with a tap rooted forage crop such as forage rape or turnip.

Insecticides do not work for redheaded pasture cockchafer because they are ground dwelling and do not get exposed to the chemical. Trials of synthetic pesticides in Victoria in the 1980’s showed no effect on control of readheaded cockchafer and there are no insecticides registered for this pest. See below for our long-term management suggestions.

The difficulty of early detection

Cockchafers feed on shallow roots, to a depth of about 15cm. As such, the major damage to plant health is often already done before any aboveground symptoms are visible.

Redheaded pasture cockchafers are traditionally monitored by making a shovel cut and counting the larvae dug up from the soil, but this approach makes it difficult to monitor large areas. Studies have shown that damage to roots can occur when mature instar larvae exceed 100/m2 but can become severe when numbers reach >300/m2 (at this stage, one indicator of a severe load is rolling back of the sward).

Research has investigated the use of sensors to detect Redheaded pasture cockchafer damage but as yet there remain no sensors commercially available.

The tell-tale signs of a cockchafer problem are bare patches, and evidence of plants with weak root structure – plants subjected to feeding may be easier to pull out (this makes further damage by livestock a concern). Damage can be isolated or, in extreme cases, observed across entire farms.

Evidence in crops is normally evident from March and can reach severe damage two to three months later. Feeding by the cockchafer will slow over winter as the larvae become less active. Severe damage to pasture production often occurs in years with a dry autumn as these conditions further stress plants that have suffered root damage.

Long term management strategies

Redheaded pasture cockchafers generally have a two-year lifecycle so outbreaks tend to occur every second year (but generations can overlap in some years). Once established they can be difficult to manage, with various cultural controls being the main option, so keeping numbers under control relies on long term management strategies.

Non-tussock forming grasses, such as ryegrass, that have shallow or more fragile root systems are most vulnerable to redheaded cockchafer damage. Therefore, rotating with crops that are less susceptible such as Phalaris sp, lucerne, tall fescue and cocksfoot is a key method for minimising redheaded cockchafers in the long term.

Diversification of the feedbase away from ryegrass to other non-grass species that are less likely to support cockchafer populations is another strategy. This may involve sowing alternative forage crops, such as forage brassica, or rotating the pasture with a cropping period.

The adult beetles prefer laying eggs in dense pasture with rank growth during the warmer weather, therefore close grazing in spring can also help against reoccurring redheaded cockchafer problems as it reduces grass density.

The damage cockchafers do to root systems will make pastures more susceptible to further damage through grazing, foraging animals (such as birds) and machinery. Methods such as controlled traffic farming and limiting machinery use on paddocks can help while pastures are fragile.

If possible, when damage is noticed to pastures in-use livestock should be removed to protect the remaining sward and help the pasture to re-establish root growth. However, when rotating crops or renovating the pasture, physical disturbance to the soil, such as tillage, or rolling can help to kill larvae in the soil.

Acknowledgement

Much of the information and management recommendations in this article have come from a detailed review published in 2014 by Dr Gordon Berg and colleagues from the biosciences research division of the Department of Environmental and Primary Industries.

Thank you to the famers and agronomists who sent in reports. Also, many thanks to Leo Mcgrane and Dr Jessica Lye for assisting with the development of this article.

Cover image: Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia