The forest-dwelling rat-kangaroo (Potorous longipes), endemic to South-Eastern Australia, had many conservationists concerned after the 2019/20 black summer bushfires that ravaged 79% of its modelled habitat range.

Initial estimates suggested that potoroo population losses could have been as high as 72% (Legge et al., 2021). With so many species of native flora and fauna suffering effects from the fires, the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) founded and funded a Bushfire Biodiversity Response and Recovery Program.

Long-footed potoroo ecology

Long-footed potoroos have an average body length of 40cm, with a tail around 32cm, and an average weight range between 1.7kg for female and 2.2kg for male adults (Seebeck, 1998). The hind feet of these small rat-kangaroos are said to be around the same length, if not larger, as their heads. They tend to create and travel through a system of undergrowth tracks, favouring protective modes of locomotion for quick escapes from predators.

Long-footed potoroos occasionally feed on fruit and small invertebrates; however they much prefer the sporocarps of a wide variety of underground fruiting fungi – in other words, these obligate fungivores have a daily diet of truffles. They often feed in pairs at night, rummaging through the dense underbrush of their preferred habitats and forming conical pits to excavate their treats of choice (Green et al., 1999). This makes them important contributors to forest ecosystems, churning leaf litter and aerating topsoil, which helps to support the symbiotic relationships between plant roots and fungi, allowing the fungi to enhance the plants’ nutrient uptake (Claridge et al., 1992).

Generally, they inhabit dense, moist forest environments at elevations anywhere between sea level and the Alps. Long-footed potoroo sightings in the East Gippsland Lowland Forest between 10m and 50m above sea level contrast with the species’ highest confirmed detection in East Gippsland, where the marsupials were spotted at 1220m and above 1500m at “The Twins” in Victoria’s Barry Mountain range. Only three populations of these endangered marsupials exist in the world, and two of them are in Victoria. The third, smaller population persists in south-east NSW, approximately 20 km north from the Victorian border in the South East Forest National Park (Broome et al. 1997). Their restricted distribution and unobtrusive habits can make this species very difficult to survey.

New research

Recent efforts to understand the impact of the 2019/20 bushfires on long-footed potoroos involved camera trapping, cage trapping and genetic analysis to understand the structure, fragmentation and genetic diversity of Victorian populations.

In this project, the team managed the collection of 51 samples from Victoria spread across the Barry Mountains in the Victorian Alps and in East Gippsland at Tulloch Ard, Manorina and Murrungowar State Forests. Data from an additional 8 previously genotyped samples were included in the study from a Federally funded post bushfire project run through the National Environmental Science Program’s (NESP) Threatened Species Recovery (TSR) hub. After data quality filtering of both sample lots, a total of 52 samples met the required standards for genetic analysis. The research yielded some interesting insights.

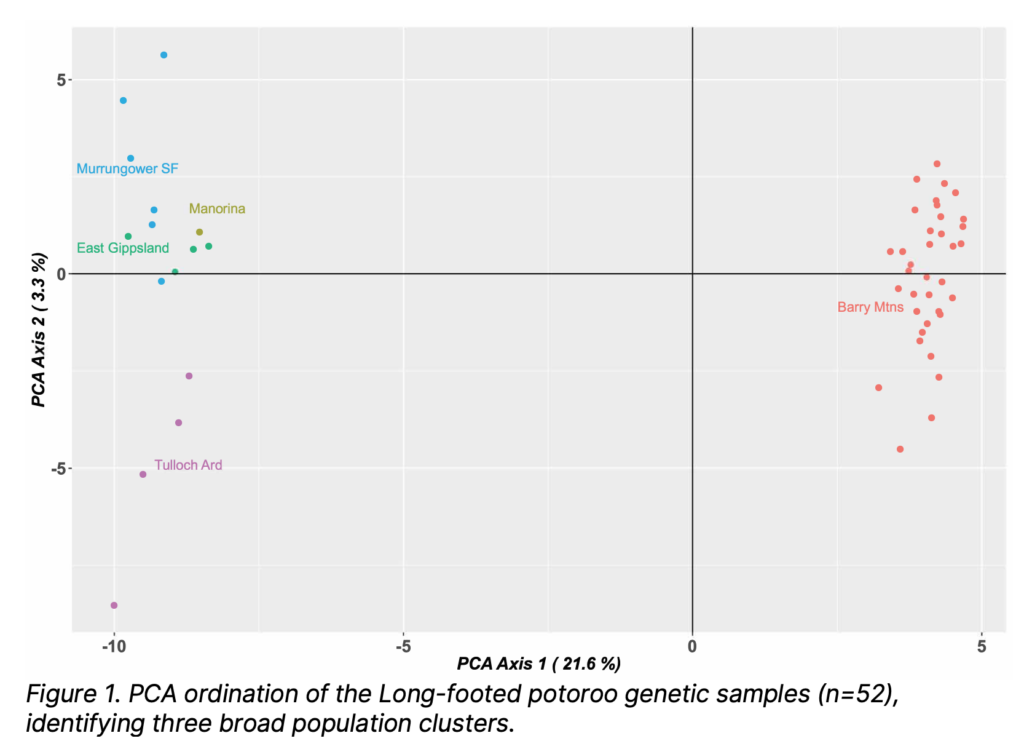

Cesar Australia scientists translated the genetic data of the 52 individual samples to visually represent their genetic closeness (Figure 1). The analysis shows significant differences in the genetic composition of the different populations, revealing three broad groups:

- The Barry Mountains samples were the most differentiated from the other populations, indicating a separation that likely predates European settlement, and represents a different gene pool to the other current populations.

- Tulloch Ard individuals are also isolated from the other samples analysed, but to a far lesser extent.

- East Gippsland, Murrungower State Forest and Manorina samples cluster together, indicating no significant genetic differentiation between these samples.

Samples from individuals collected in East Gippsland and the Murrungower State Forest had the highest relative diversity, based on allelic richness and heterozygosity. The populations in the Barry Mountains had the highest levels of inbreeding (which means lower genetic diversity).

Genetic data supports conservation efforts

Historically, long-footed potoroos suffered range contraction following the reduction in habitat from European farming practices and urbanisation, and the onslaught of invasive predators such as foxes, wild dogs and feral cats. More recently, populations have experienced further declines due the effects of climate change through drought and large scale fires, such as the great alpine fires in 2003 and 2006, and the recent black summer bushfires in 2019/20.

In efforts to increase the availability of habitat, the Southern Ark and Barry Mountains fox control programs have expanded to deliver an additional 207,000 hectares of control (DELWP, 2022), providing greater protection to long-footed potoroo populations from the threat of fox predation.

Genetic mixing strategies, such as introductions of individuals from different populations, may be a solution to increase diversity, given that genetic bottlenecks causing reductions in genetic diversity generally play out over several generations. One such genetic management option might include adding diversity to the Barry Mountains population with either ex-situ genetic mixing to establish a viable genetically improved population to supplement the Barry Mountains population. Another option may involve the translocation of Long-footed potoroo individuals from East Gippsland into the Barry Mountains population. These strategies, however, require continued monitoring and genetic analysis in order to be successful.

The genetics of the Tulloch Ard samples were different from the other East Gippsland samples and indeed separated by the Snowy River, though it is not clear how recently the Tulloch Ard and further East Gippsland population were separated. which may pose a barrier to dispersal (gene flow) in this region. Situations like these may potentially benefit from investment in wildlife corridors, which would enable the movement of animals (and genetics!) and the continuation of viable populations.

This strategy requires further investigation to determine its suitability for the region and the species’ ecology.

Recommendations from the research

Cesar Australia scientists recommend further sampling across the range of the Long-footed potoroo to provide a more complete picture of population structure and genetic health, and to help inform future management of this endangered species.

There is also a need for more genetic sampling at sites east of the Snowy River within 10kms of the Tulloch Ard population, where Long-footed potoroos have been detected on cameras, but no genetic material has been collected.

By continuing with the genetic monitoring of these Victorian populations, with a keen eye on the isolated group in the Barry Mountains, the broader team hope to develop and implement strategies that increase the population’s resilience to impacts such as bushfires and prevent the further decline of the genetic diversity of the Barry Mountains population.

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of this report, Dr Andrew Weeks & Peter Kriesner, as well as Anthony van Rooyen for his sample processing consultations.

We would also like to thank Maria Cardoso and Elizabeth Wemyss (DELWP) for managing the collection of samples for this project and ongoing discussions. We’re grateful for the experience of Tony Mitchell, Jerry Alexander and Andy Murray, which was instrumental in preparing and delivering the on-ground trapping and tissue collection. We thank Greta Frankham and Mark Eldridge (Australian Museum) for support and providing access to the DArT data on P. longipes individuals from the NESP TSR post bushfire project through Bioplatforms Australia.

This project received funding from the Victorian Government’s DELWP Bushfire Biodiversity Response and Recovery program to support Victoria’s bushfire impacted wildlife and biodiversity. The Commonwealth Government’s Bushfire Recovery package for wildlife and their habitats supports this program.

This article draws on findings from:

Legge S, Woinarski JCZ, Garnett ST, Geyle HM et al. 2021. Estimate of the impacts of the 2019-20 fires on populations of native animal species. Threatened Species Recovery Hub, Australia.

Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (2022) Victoria’s bushfire emergency: Biodiversity response and recovery, Victoria’s bushfire emergency: Biodiversity response and recovery. DELWP. Available at: https://www.wildlife.vic.gov.au/home/biodiversity-bushfire-response-and-recovery. Accessed: December 15, 2022.

Nunan D., Henry S., and Tennant P. (1998) Long-footed Potoroo Potorous longipes (Seebeck and Johnston, 1980) Recovery Plan. Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Orbost, Victoria.

Green, K., Tory, M.K., Mitchell, A.T., Tennant, P. and May, T.W. (1999). The diet of the Long-footed Potoroo (Potorous longipes). Australian Journal of Ecology. 24, 151-156.

Claridge, A.W. (1992). Is the relationship among mycophagous marsupials, mycorrhizal fungi and plants dependent on fire? Australian Journal of Ecology 17, 223-25.

Cover image: Long footed potoroo