Blue oat mite

Penthaleus spp.

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

Blue oat mites are major agricultural pests of southern Australia attacking various pasture, vegetable and crop plants. There are three pest species of blue oat mites that differ in their distributions, pesticide tolerances and host plant preferences. Spring spraying using TIMERITE® against blue oat mites is not recommended as it is largely ineffective.

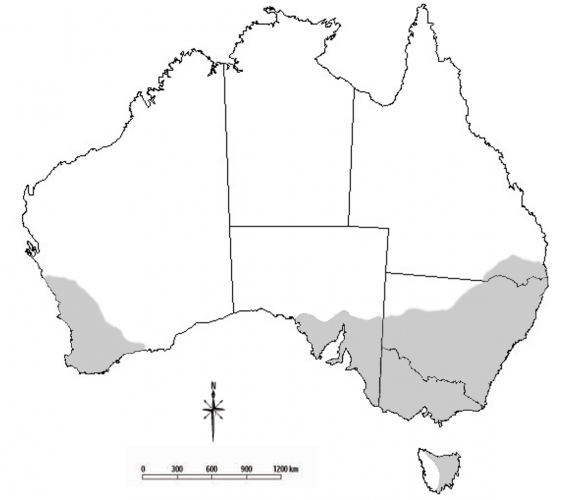

Occurrence Top

Blue oat mites are important crop and pasture pests in southern Australia. They are commonly found in Mediterranean climates of Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia and eastern Tasmania. They are also found in parts of southern Queensland. There are three main species of blue oat mite; Penthaleus major, Penthaleus falcatus and Penthaleus tectus. These species differ in their distributions.

Description Top

The three recognised pest species of blue oat mite are morphologically very similar. A microscope is required to distinguish the morphological differences between Penthaleus major, Penthaleus falcatus and Penthaleus tectus. P. major has long setae arranged in four to five longitudinal rows, while P. falcatus has a higher number of short setae scattered irregularly. P. tectus has setae of medium length and number.

Adult blue oat mite are approximately 1 mm in length and have a blue-black body with a distinctive red mark on their back. They have eight red-orange legs. The nymphs are pinkish-orange in colour with six legs on hatching, but soon change colour to brownish and then green, before reaching the adult stage.

There are three morphologically similar species of blue oat mites that differ in their distributions, pesticide tolerances and host plant preferences.

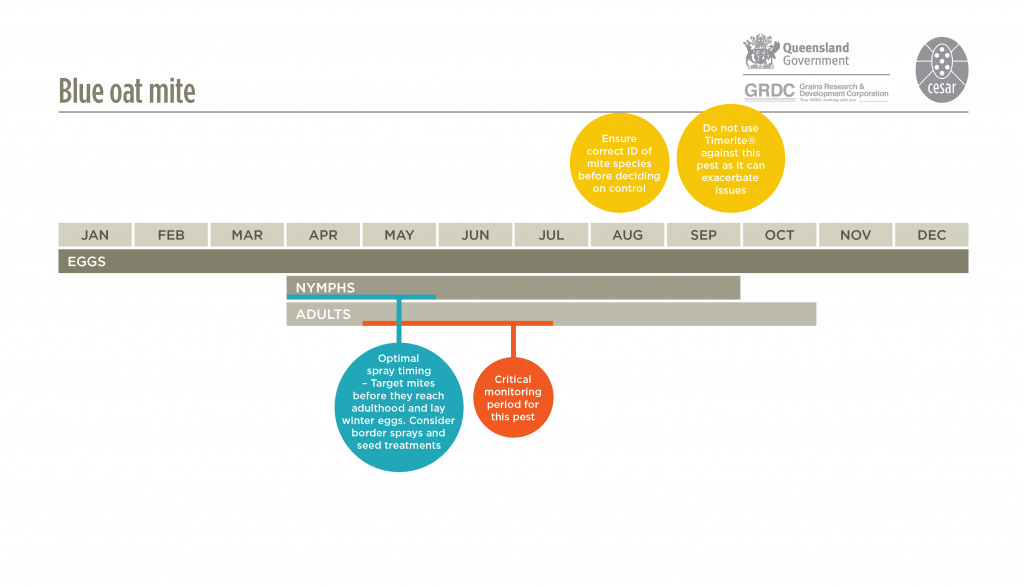

Lifecycle Top

Blue oat mites are active in the cool wet part of the year, usually between April and late October. During this time they pass through two or three generations, with each generation lasting eight to ten weeks. They spend the remaining months protected as diapause or over-summering eggs that are resistant to the heat and desiccation of summer. These eggs hatch in autumn following cool temperatures and adequate rainfall, when conditions are optimal for mite survival. The climatic conditions are similar, but probably different to those that trigger egg hatch of redlegged earth mites. Swarms of young mites will then attack emerging crop and pasture seedlings.

Female mites deposit eggs either singly or in clusters of three to six on the leaves, stems and roots of food plants or on the soil surface.

Blue oat mites reproduce asexually. This mode of reproduction results in populations made up of female ‘clones’ that can respond differently to environmental and chemical conditions than mites reproducing sexually. This may influence the likelihood of populations developing resistance and means blue oat mite populations could respond differently to control strategies.

Eggs hatch in autumn following cool temperatures and adequate rainfall. Swarms of mites attack emerging crop and pasture seedlings.

Behaviour Top

Blue oat mites often coexist with redlegged earth mites and both are typically active from autumn to late spring. Blue oat mites spend the majority of their time on the soil surface, rather than on the foliage of plants. They are most active during the cooler parts of the day, tending to feed in the mornings and in cloudy weather (particularly in spring). They seek protection during the warmer part of the day on moist soil surfaces or under leaf litter, and may even dig into the soil under extreme conditions.

Similar to Top

Redlegged earth mites, Balaustium mites and Bryobia mites. The orange-red patch on the back of blue oat mites is unique and generally quite conspicuous when viewed with a hand lens.

Crops attacked Top

All crops and pastures are vulnerable to attack and they are most susceptible at the seedling stage. Host plant preferences for the three species are as follows: P. major – pastures, cereals and pulses; P. falcatus – mainly found on canola, but also on broad-leaved weeds such as Paterson’s curse, bristly ox-tongue, smooth cat’s-ear and capeweed; P. tectus – mainly found on cereals, but also on pastures and some pulses.

Damage Top

Feeding causes silvering or white discoloration of leaves and distortion, or shrivelling in severe infestations. Affected seedlings can die at emergence with high mite populations. Unlike redlegged earth mites, blue oat mites typically feed singularly or in very small groups.

Feeding causes silvering or white discoloration of leaves, and distortion or shrivelling in severe infestations. Mites feed singularly and not in large groups.

Monitor Top

Inspect susceptible pastures and crops from autumn to spring for the presence of mites and evidence of damage. It is important to inspect crops regularly in the first three to five weeks after sowing. Mites are best detected feeding on the leaves in the morning or on overcast days. If mites are not observed on plant material, inspect the soil for mites. An effective way to sample mites is to use a standard petrol powered garden blower/vacuum machine. A fine sieve or stocking is placed over the end of the suction pipe to trap mites vacuumed from plants and the soil surface.

Mites are most reliably detected on leaves in the morning or on overcast days.

Economic thresholds Top

There are no economic thresholds established for this pest.

Management options Top

Biological

French Anystis mites can suppress populations in some pastures. Snout mites and other predatory mites are also effective natural enemies. Leaving shelterbelts or refuges between paddocks will help maintain natural enemy populations.

Cultural

Rotate paddocks with non-preferred crops (P. major – canola; P. tectus – chickpeas; P. falcatus – wheat, barley). Pre- and post- sowing weed management (particularly broad-leafed weeds) is important.

Predatory mites can be effective natural enemies of blue oat mites and non-preferred crops and weed management helps to control these mites.

Chemical

Chemicals are the most common method of control against earth mites. Unfortunately, all currently registered pesticides are only effective against the active stages of mites; they do not kill mite eggs. While a number of chemicals are registered in pastures and crops, differences in tolerance levels between species complicates management of blue oat mites. P. falcatus has a higher tolerance to a range of pesticides and this is often responsible for chemical control failures. Ensure pesticide sprays are applied at the full registered rate. P. major and P. tectus have lower tolerances to pesticides and are more easily controlled.

For low-moderate mite populations, insecticide seed dressings are an effective method. Avoid prophylactic sprays; apply insecticides only if control is warranted and if you are sure of the mite identity. Pesticides used at or after sowing should be applied within three weeks of the first appearance of mites, before adults commence laying eggs. Spring spraying using TIMERITE® is largely ineffective against blue oat mites and is not recommended.

While a number of chemicals are registered in pastures and crops, differences in tolerance levels between species complicates management of blue oat mites.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Sandra Hangartner.

References/Further Reading Top

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: Identification and Control. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. 2012. I SPY. Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA), the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) and cesar Pty Ltd.

Hill MP, Hoffmann AA, McColl SA and Umina PA. 2012. Distribution of cryptic blue oat mite species in Australia: current and future climate conditions. Agricultural and Forest Entomology 14: 127-137.

Merton E, McDonald G and Hoffmann A. 1995. Proceedings of the 2nd national workshop on redlegged earth mite, lucerne flea and blue oat mite, held in Rutherglen, Victoria, Australia, October 1994. Plant Protection 10: 65-66.

Michael PJ, Dutch ME and Pekin CJ. 1991. A review of the predators of redlegged earth mite, blue oat mite and lucerne flea. Plant Protection Quarterly 6:178-180.

Micic S, Strickland G, Weeks A, Hoffmann A, Nash M, Henry K, Bellati J and Umina P. 2008. Pests of establishing crops in southern Australia: a review of their biology and management options. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 48: 1560-1573.

Murray DAH, Clarke MB and Ronning. 2013. Estimating invertebrate pest losses in six major Australian grain crops. Australian Journal of Entomology 52: 227-241.

Robinson MT and AA Hoffmann. 2001. The pest status and distribution of three cryptic blue oat mite species (Penthaleus spp.) and redlegged earth mite (Halotydeus destructor) in southeastern Australia. Experimental & Applied Acarology 25: 699-716.

Umina PA and Hoffmann AA. 1999. Tolerance of cryptic species of blue oat mites (Penthaleus spp.) and the redlegged earth mite (Halotydeus destructor) to pesticides. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 39: 621-628.

Umina P and Hoffmann AA. 2003. Diapause and implications for control of Penthaleus species and Halotydeus destructor (Acari: Penthaleidae) in southeastern Australia. Experimental and Applied Acarology 31: 209-223.

Umina PA and Hoffmann AA. 2004. Plant host associations of Penthaleus species and Halotydeus destructor (Acari: Penthaleidae) and implications for integrated pest management. Experimental and Applied Acarology 33: 1-20.

Umina PA, Hoffmann AA and Weeks AR. 2004. Biology, ecology and control of the Penthaleus species complex (Acari: Penthaleidae). Experimental and Applied Acarology 34: 211-237.

Umina P. 2007. Blue Oat Mite. Department of Primary Industries Victoria. http://www.depi.vic.gov.au/agriculture-and-food/pests-diseases-and-weeds/pest-insects-and-mites/blue-oat-mite

Umina PA, Arthur AL, McColl SA, Hoffmann AA and Roberts JMK. 2010. Selective control of mite and collembolan pests of pastures and grain crops in Australia. Crop Protection 29: 190-196.

Weeks AR, Fripp YJ and Hoffmann AA. 1995. Genetic structure of Halotydeus destructor and Penthaleus major populations in Victoria (Acari: Penthaleidae). Experimental and Applied Acarology 19: 633-646.

Weeks AR and Hoffmann AA. 1999. The biology of Penthaleus species in southeastern Australia. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 92: 179-189.

Weeks AR and Hoffmann AA. 2000. Competitive Interactions Between Two Pest Species of Earth Mites, Halotydeus destructor and Penthaleus major (Acarina: Penthaleidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 93: 1183-1191.

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 2015 | 1.0 | Paul Umina (cesar) and Sandra Hangartner | Alana Govender (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.