True wireworm

Elateridae (Family)

Other common names

Click beetle

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

True wireworms are similar in appearance to false wireworms but can be mostly distinguished by their flattened head and often by the presence of a flattened, serrated tail plate. They are found across most states of Australia and the larvae are soil dwelling, being most common in wetter soils. They usually attack cereals but occasionally damage pulses and canola. Early detection, before sowing, is important if control is to be successful.

Post-emergence sprays are not effective.

Occurrence Top

There are numerous true wireworm species in Australia and are generally only a sporadic pest. Native to Australia, they are found across most states.

Description Top

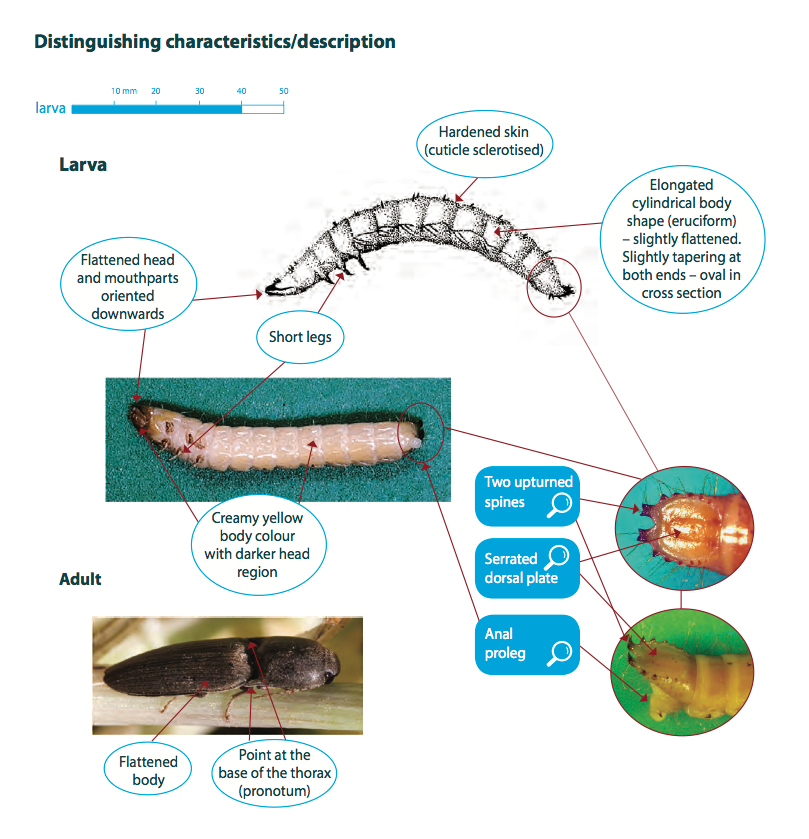

Larvae typically grow to 15-40 mm long and range in colour from creamy-yellow to red-brown. They have soft, elongated and cylindrical bodies that are somewhat flattened towards the head. The wedge-shaped head is usually darker in colour.

The most common species (Agrypnus spp.) have a flattened, serrated dorsal plate on the end of the last body segment and a pair of upturned tail processes protruding from the plate. True wireworm larvae also possess an anal proleg on the last segment. Adults are known as click beetles, and are dark brown to black, elongated and 9-13 mm in length. They are torpedo-shaped, and if placed on their backs will flip over making a distinctive click sound.

Lifecycle Top

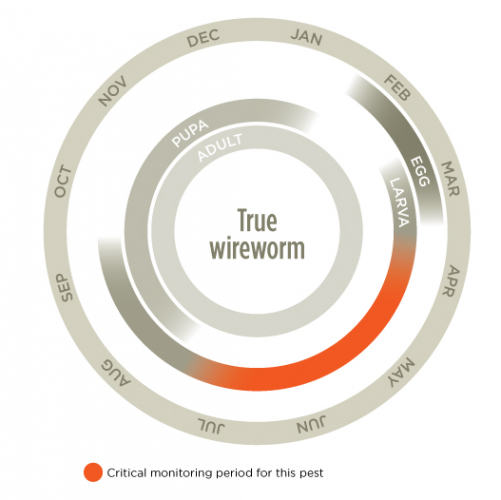

The lifecycle of many true wireworms is poorly understood. Adults are typically found in summer and autumn and shelter under the bark of trees during winter. Adult beetles often lay eggs in late summer. Larvae emerge in autumn and most damage to crops occurs from April to August. Depending on the species true wireworms can have one or several generations each year, although mostly one.

Behaviour Top

Larvae are soil dwelling and slow moving. Adults are known as ‘click’ beetles due to their habit of springing into the air with a loud click when placed on their backs.

Similar to Top

Larvae are similar to false wireworms, including the eastern false wireworm and the vegetable beetle, as well as carabid beetle larvae. Carabid larvae have distinctive pincer-like mandibles on the head.

Crops attacked Top

Largely confined to cereals such as wheat, barley, triticale and oats, although occasionally reported in some pulse crops and canola. They can be found more commonly in grassy pastures.

True wireworm pest status is reportedly minor, restricted and sporadic.

Damage Top

Larvae attack germinating seed and underground stems of cereals and may also feed on the roots of seedlings. Germinating seedlings can be ring-barked and hypocotyls severed just below the soil surface, causing wilting and seedling death. Damage can result in thinning and bare patches within crops, and severe damage may require re-sowing.

The risk period is at the seeding stage shortly after plants emerge.

Monitor Top

True wireworms prefer low-lying, poorly drained paddocks and are most common in wetter soils. Check paddocks prior to sowing by digging to a depth that includes the moist soil layer where larvae will be present, and at least 10cm. Repeat this process a number of times across the paddock to get a representative sample. Paddocks coming out of long-term pasture are at most risk.

Germinating seed baits can be used immediately following the autumn break. Soak wheat seed in water to initiate germination, then bury several seeds under 1 cm of soil at each corner of a 5 x 5 m square grid, marking each with a flag. Immediately after seedling emergence, re-visit the bait site, dig up the plants and count the number of larvae present. Repeat this at 5 locations per 100 ha to obtain a reasonable estimate of numbers.

As wireworms can be found beneath plant debris, check under stubble before sowing.

Economic thresholds Top

An average of 10 larvae/m2 may warrant control. Average densities of 40 larvae/m2 can cause enough damage to require re-sowing (Bellati et al. 2010).

Management options Top

Biological

Carabid beetles and larvae are known predators of soil-dwelling insects including true wireworm larvae. However, they are usually not present in high enough numbers to effectively control large pest populations. Additional natural enemies include spiders, native earwigs, other predatory beetles and birds after cultivation.

Cultural

Stubble retention and minimum tillage are thought to contribute to the build-up of true wireworm populations. Removal of stubble before egg laying, or cultivating soil in summer and autumn will discourage egg laying and reduce larvae numbers. Consider sowing canola or a pulse crop if high populations of this pest are present.

Chemical

Several insecticide seed treatments are registered for true wireworm control in certain broadacre crops in some states. In addition, chlorpyrifos and some other products have general registration against true wireworms in certain broadacre crops in some states. However note that effective control of wireworms is generally not possible after sowing. The insecticide needs to be applied in furrow.

Wireworms can only be controlled if they are detected before sowing.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI).

References/Further Reading Top

Allen, P. 1986. Wireworms and false wireworms in cereal crops. FactSheet 24/85. Department of Agriculture South Australia, Adelaide.

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: Identification and Control. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. 2012. I SPY Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA), the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) and cesar Pty Ltd.

Henry K, Bellati J, Umina P and Wurst M. 2008. Crop Insects: the Ute Guide Southern Grain Belt Edition. Government of South Australia PIRSA and GRDC.

McDonald G. 1995. Wireworms and false wireworms in field crops. Agriculture Notes (Ag0411). Victorian Department of Primary Industries. http://www.depi.vic.gov.au/agriculture-and-food/pests-diseases-and-weeds/pest-insects-and-mites/wireworms-and-false-wireworms

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 2015 | 1.0 | Bill Kimber (SARDI) | Garry McDonald (cesar) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.