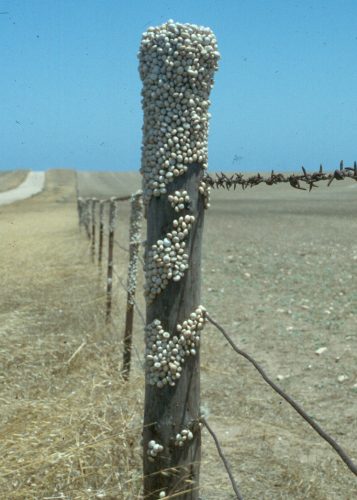

Vineyard snail

Cernuella virgata

Other common names

Common white snail

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

Vineyard or common white snails feed on organic matter that accumulates on the soil surface but may feed on young crop plants. However, they are a considered a serious pest because they contaminate grain during harvest and can clog and damage harvest machinery. They over-summer off the soil surface on stubble, posts and vegetation.

Cultural management of stubble in January and February is an important control strategy.

Occurrence Top

An introduced snail from the Mediterranean region of Europe, the vineyard or common white snail is found throughout the agricultural districts of South Australia and the Victorian Mallee and Wimmera. It occurs in New South Wales, Western Australia and eastern Tasmania. They favour calcareous and highly alkaline soils which influences their regional distribution.

Description Top

Mature snails have shells that are from 10 to 20 mm in diameter. The white shell is coiled and while most individuals have a brown band around the spiral, others lack this banding and are completely white. The umbilicus (hole in the centre of the shell) is open and circular. If viewed under magnification, there are regular and straight scratches across the shell.

Lifecycle Top

As snails are hermaphrodites each snail has both male and female reproductive organs. Therefore every snail has the potential to lay eggs after mating. Snails lay hundreds of eggs each season and if conditions are favourable, numbers can increase rapidly. Soil moisture content determines when egg laying begins. The snails over-summer (aestivate) on stubble, fence posts, weeds and other vegetation to avoid the high soil surface temperatures of summer. Moisture, either from heavy dews or rainfall, will trigger snails to become active and descend to the soil surface. Autumn moisture also encourages snails to become more active on the soil surface. It appears autumn rainfall triggers mating, then feeding if moisture persists. If the soil remains moist egg laying can commence two weeks after mating. Most egg laying occurs in autumn or early winter although some laying continues to early spring. Eggs hatch after about 2-3 weeks. After steady growth through winter and spring the snails aestivate through the following summer. Vineyard or common white snails can have either an annual or biennial lifecycle. Increased autumn rainfall is the best indicator of increased spring populations.

They are, nonetheless, opportunistic breeders. Previous wet summers have indicated that, when conditions are suitable, breeding can occur in summer.

Increased autumn rainfall is the best indicator of increased spring populations.

Similar to Top

These snails can be confused with the white Italian snail but can be separated by the difference in the umbilicus. White Italian snails have an umbilicus that is half closed off and not circular.

Crops attacked Top

Field crops including wheat, barley, oats, field peas, faba beans, and canola, as well as pastures. Vineyard snails are a significant pest primarily because they contaminate grain during harvest while also cogging and damaging harvest machinery.

Damage Top

While mainly feeding on organic matter on the soil surface, they may damage young plants. In some areas, there is also evidence that the snail may impact native flora and grasslands. Typical damage includes shredded leaves, by the snail’s rasping mouthpart, often defoliating plants.

Monitor Top

Concentrate monitoring between January and April. Continue to monitor throughout the growing season to detect snail movement from edges of paddocks into crops.

Suggested key monitoring times are:

- Jan-Feb, assess stubble management options

- Mar-April, assess for burning and/or baiting

- 3-4 weeks prior to harvest, assess for header alterations

- Count snails before considering control options and repeat 7 days after control to record effectiveness.

Early identification of population growth is essential for rapid control. The importance of monitoring to determine feeding activity cannot be over emphasised.

Economic thresholds Top

The use of thresholds for snails is not relevant, as good snail management requires population reduction at every opportunity.

Management options Top

Biological

There can be some predation by birds and lizards.

Cultural

There are several cultural control options. These appear in detail in Bash’Em Burn’Em Bait’Em – Integrated snail management in crops and pastures. In summary there are two approaches to cultural control.

• Bash’Em. As snails over-summer on any object above the soil surface to escape high summer soil temperatures, stubble management by cabling, rolling or slashing is designed to bring the snails to the soil surface where they desiccate and die. The higher the temperature when these processes are carried out, the more likely that snails will die. For effectiveness, air temperatures should be above 35°C. Snail numbers can be reduced by as much as 50% to 70% through using stubble management.

• Burn’Em. This is the most effective method of snail control pre-breeding. An even burn is most effective. As snails are often beneath rocks, these should be turned before burning, and summer weeds should be browned-off. While burning stubble is seen as advantageous in destroying weed seeds, stubble harboured diseases and snails, it is also detrimental in that it destroys beneficial soil organisms and reduces organic matter. Burning may reduce snail numbers by up to 99%. Burn only when fire restrictions permit.

Snails have been found along all major transport routes between South and Western Australia, especially in camping grounds and at intersections along these roads. This suggests snails have become proficient hitch-hikers and are moving between regions on transport.

To avoid moving snails from infested to clean areas, farm machinery and produce such as hay should be inspected and if necessary cleaned of snails.

Chemical

Commercial snail baits are available for snail control. Choice of bait is dependent on which products are registered for use in your state. Consult the product label. Label rates must be adhered to.

- Timing of application is critical for success and is dependent on snail feeding.

- Control weeds that offer a refuge for snails before baiting.

- Commence baiting following rain or heavy dews in March as snails may not always feed after summer rain.

- Baiting before seeding is more effective as the bait will be the only food available.

- Ensure baits are spread evenly.

- Trials have shown that if using a fertilizer spreader, baits can only be spread 18-24 metres and it is important to ensure total coverage.

- Monitor snail numbers across the paddock and adjust bait rates accordingly.

- Bran based baits need to be applied regularly, at least every two weeks. More expensive extruded products last up to a month.

- After spreading bait, check the spread and the amount of bait used. This will indicate if follow-up baiting is required.

- Follow-up moisture may result in egg laying within 2 weeks and it is essential to apply bait before this occurs.

Controlling snails before egg laying commences is essential.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Helen DeGraaf (SARDI) and Bill Kimber (SARDI).

References/Further Reading Top

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: Identification and Control. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Baker G. and Hopkins D (eds). 2003. Bash’Em Burn’Em Bait’Em – Integrated snail management in crops and pastures. GRDC, SARDI, SAGIT https://www.grdc.com.au/uploads/documents/Snails%20BBB.pdf

Henry K, Bellati J, Umina P and Wurst M. 2008. Crop Insects: the Ute Guide Southern Grain Belt Edition. Government of South Australia PIRSA and GRDC.

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| February 2015 | 1.0 | Helen DeGraaf (SARDI) and Bill Kimber (SARDI) | Michael Nash (SARDI) and Garry McDonald (cesar) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.